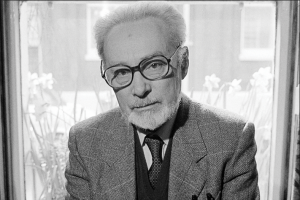

ITALIAN PORTRAITS Primo Levi, Writing about the Horror

Once in an interview, Primo Levi said, “I am a chemist. But my existence was marked by two fundamental facts. The first is imprisonment at Auschwitz. The second is having written about my imprisonment at Auschwitz.”

In January 1945, Primo Levi was finally liberated from Auschwitz after eleven months in the death camp, not knowing that his experiences there would consume him for the rest of his life.

Levi was born into an Italian Jewish family in Turin, Italy on July 31, 1919. Aside from a period during the Second World War, he spent the majority of his life in the apartment where he was born, which was also the place in which he died in 1987. Although he and his family were highly assimilated, the anti-Semitic racial laws passed in 1938 and ensuing persecution made Levi’s Jewishness a defining and primary attribute of his personality. “This dual experience, the racial laws and the extermination camp, stamped me the way you stamp a steel plate,” Levi remembered. “At this point I’m a Jew, they’ve sewn the star of David on me and not only on my clothes.” That said, life continued relatively securely for the Jews of Italy during WWII, but only until the fall of Mussolini in July 1943. After his fall, Germany immediately occupied northern and central Italy, which had initially been an ally of Nazi Germany.

Under German occupation, Primo Levi’s mother and sister went into hiding while he joined a partisan group, which was soon captured by Fascists. It was because of this and the discovery of his religion that Levi was sent to a transit camp at Fossoli, Italy. Just weeks after his arrival, the Germans emptied the camp of Jews deporting them to Auschwitz.

Levi viewed Auschwitz “as a complex system in which the Nazis had devised a process of dehumanization that pitted victims against each other in an animalistic fight for survival. By oppressing their victims,” writes Levi, “the Nazis themselves became dehumanized, because to act inhumanely, is to deny one’s own humanity. The Nazis sought to annihilate us first as men in order to kill us more slowly afterwards.” After eleven months in the camp, Primo Levi was among the very few Italian Jews fortunate enough to survive. Eleven months in Auschwitz may seem like a short amount of time when compared to the many years of the camp’s activity. For Primo Levi, however, eleven months in Auschwitz was enough to irreversibly change and determine the rest of his life, even though the Nazi’s failed to take it.

Approximately nine months after being liberated from Auschwitz, Levi finally returned home. Barely recognizable due to extreme exhaustion and malnourishment, it was evident that Levi had been shaken by the traumas he had endured. Levi started to write almost immediately upon his return. In many of Levi’s works, he describes his postwar thoughts and feelings. Among the most inextinguishable of these emotions, was probably his feeling of guilt for surviving Auschwitz where he had been surrounded by death and had witnessed the loss of so many innocent lives.

Survivor’s guilt does not only consist of feeling guilty for surviving when so many others did not. Such guilt also stems from the near impossibility of expressing and communicating the depth of barbarity and viciousness suffered by those who did not survive.

After initially falling on deaf ears, his books have become central texts of Holocaust literature with their mix of analytical clarity, philosophical reflection, and deep humanity. Diverse in genre and subject matter, they range from the canonical witness testimony of “Se questo è un uomo” (Survival in Auschwitz) to the science fiction short stories in “Storie naturali” (Natural Histories), from the picaresque odyssey of “La tregua” (The Reawkening) to the philosophical explorations of the Holocaust in “I sommersi e i salvati” (The Drowned and the Saved). Levi considered it his duty to teach his and later generations about the Holocaust and the danger we still run of falling into similar patterns of violence.

*Danielle Rockman is a student at Muhlenberg College (Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA).