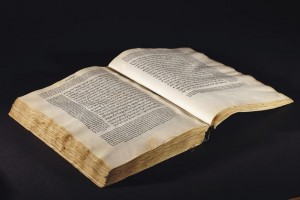

NEWS Italian Torah Book Fetches Record at Paris Auction

During the 15th century, Italian printers produced several versions of the Torah, all considered of huge value. But the Humash printed in Bologna in 1482 and sold by Christie’s in Paris last week has won the highest price ever fetched in the whole world by a book printed in Hebrew. Close to three million euros, it won more than any other printed book known to ever have been sold in France.

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type printing had a huge impact on Jewish life: the diffusion of written texts helped enormously the transmission of Jewish culture, and printing served as a major catalyst for Jewish survival. Finally, through the dissemination of the printed book, Jews around the world could figuratively and literally stay on the same page, across the globe.

Abraham Conat was an Italian Jewish physician, and one of the earliest printers of Hebrew books. He referred to the new technology as “writing with many pens without a miracle”. Despite ecclesiastical pressure and political intolerance aimed to exclude them from the field, Jews in Italy established printing houses wherever and whenever they could and their influence in printing has been remarkable. The first one where in Mantua, Piove di Sacco and Rome, but soon followed Soncino, Bologna, Brescia and many others.

“This volume is a landmark in the history of printing – said Christoph Auvermann, head of the books and manuscripts department at Christie’s in Paris before the auction – It was a major technical achievement to be able to produce this book.”

“This volume is a landmark in the history of printing – said Christoph Auvermann, head of the books and manuscripts department at Christie’s in Paris before the auction – It was a major technical achievement to be able to produce this book.”

Christie’s, in fact, has underestimated the item’s worth, expecting to fetch about 1.5 million euros. Two other copies of the same rare edition had already come to auction: the first in 1970, printed on vellum as this last one, and the other in 1998, but printed on paper and missing eight pages. It is one of the peculiarities of the 1482 Bologna edition: apparently the main run was on vellum and the paper issue was smaller by at least 50 copies, an unusual even if not unique proportion in early Hebrew publishing.

This book, which has become a model for all subsequent printed editions of the Torah, is from every point of view a turning point in the history of printing and in the study of the Hebrew text. This Humash – so is called the Torah when it does not take the form of a scroll – comes with the Aramaic paraphrase and commentary by Rashi (Solomon ben Isaac). It is the first appearance in print of the ancient targum attributed to Onkelos, the Targum Onkelos, but Rashi’s commentary had been first published in Rome some dozen years earlier.

As the sofer Amedeo Spagnoletto explains, the liturgical readings of the Torah in synagogue must be done from manuscript scrolls: “The Bologna editio princeps, combining the text with the Aramaic targum and Rashi’s commentary, was probably aimed at an educational market, the codex form being far more efficient for study.”

It was also the very first time that full vocalization and cantillation marks have been added to the text. A landmark in the history of Hebrew book production for its pioneering technique of casting and setting accents. In fact an earlier typographical attempt at adding Hebrew accents, in a 1477 folio edition of the Psalms printed by a consortium of typographers in Northern Italy, was aborted after a few pages.

Abraham ben Hayim, the printer, may have started as a bookbinder in Pesaro, but in Bologna worked for Joseph ben Abraham, a member of the influential Jewish banking family Caravita. His first recorded printing press stood at Ferrara in 1477, and produced two books, beginning with Levi ben Gershom’s Be’ur sefer lyov (Commentary on the Book of Job), financed by Nathan of Salò. Then it completed Jacob ben Asher’s Tur yoreh de’ah (Teacher of Knowledge), which had been started at the press of Abraham ben Solomon Conat, in Mantua.

The volume – completed on Jewish year 5242, in the month of Adar I – has been in an Italian library until at least the mid 17th century. This is testified by the exceptional presence on the book of the signatures of three 16th and 17th century censors: Luigi da Bologna, Dominican friar, in March 1599; Camillo Jaghel in 1613 and Fra Renato da Modena in 1626. After that, there is no evidence of more recent provenance, except for the 18th-century binding, which is probably French. And the precious volume was, in fact, part of a French Private Collection.