“My mother’s face and Christian Boltanski”, when art and memory become a family matter

Christian Boltanski, the French conceptual artist deceased a few days ago, was known internationally for his work exploring notions of memory, loss and cultural history through a process of free artistic appropriation. But what does it mean when your own mother and your most intimate memories are part of this process?

After having discovered her mother’s face in a class photo taken in Vienna in 1931 on the cover of the book Die Mazzensinsel, the Italian scholar Elèna Mortara finds it again in Altar to the Chases High School, one of the best-known installations by Boltanski.

She confronts these very delicate issues in the essay “Crowded-in (Post)memory: Of My Mother’s Face as a Young Girl, and Other Stories” of which we publish here an excerpt. The essay was published in Past (Im)Perfect Continuous. Trans-Cultural Articulations of the Postmemory of WWII, curated by Alice Balestrini (Sapienza University). A free version of the book, released in June, can be downloaded here.

By Elèna Mortara*

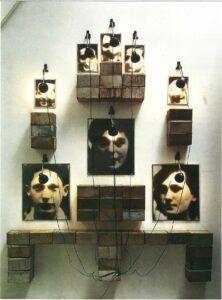

[…] It was at about that time, in 1986-88, that another artist of this generation, Christian Boltanski, a by-now famous contemporary French avant-garde artist, born from a Jewish-born father and a Catholic mother in 1944, began creating his big altar-like installations made of tin boxes and large, violently illuminated photographs of faces of Jewish school kids, as a reminder of the loss and tragic mass murder of innocent Jews by the Nazis.

The visual document that Christian Boltanski used for his most famous series of memorial artwork on the Holocaust—the culmination of a longer series of installations started in 1985 and grouped by him under the general title of Leçons de ténèbres (Lessons of Darkness)—was … my mother’s class photograph of 1931, that impressive photograph from Chajes High School, which Boltanski also found in the book Die Mazzesinsel, published two years earlier.

In this series of installations, originally called Autel de Licée Chases (1986-1988), and in English usually named Altar to the Chases High School, it was my mother’s serious face as a young girl that Boltanski most often selected among the others and included in his various “altars,” to represent that lost and annihilated world confronted with premature death and the tragedy of the Shoah. I discovered the way in which my mother’s young face had been transformed into a universal symbol of loss and mortality only several years later.

In 2005, my brother Carlo Andrea, who had already happened to come across one of those amazing installations in an exhibition abroad, told me and our sister about an Italian publication on contemporary art, Grandi arti contemporanee by Gabriele Crepaldi, where Boltanski was represented by this single work of his, the Altar to the Chases High School (Altare Chases; Crepaldi 34) (Fig. 3). And that’s probably how I first saw my mother’s enlarged face as a young girl fixed on the right base of an artistic altar.

In the United States, Boltanski’s Lessons of Darkness were first exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, in 1988.8 When the exhibition reached the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, in 1988-1989, a review of the exhibit by Kay Larson mentioned Boltanski’s Licée Chases series as his most recent work.

Larson describes the “bloated faces” of the photographs used in the new installations, specifying their source from a book on Vienna’s Jews and then commenting: “The knowledge that these children were real, that they may still be walking among us unrecognized and adult—unless they all died in the concentration camps—moves Boltanski out of solipsism.”

Larson describes the “bloated faces” of the photographs used in the new installations, specifying their source from a book on Vienna’s Jews and then commenting: “The knowledge that these children were real, that they may still be walking among us unrecognized and adult—unless they all died in the concentration camps—moves Boltanski out of solipsism.”

The sepulchral atmosphere of the artwork is finally thus synthesized: In the series on the students of the Chases High School, Boltanski mounts small floodlights in front of the photographs and turns them against their subjects; the faces nearly drown in a sepulchral drenching of light. The lights, literal vehicles of illumination, are also potentially inquisitorial, vacillating between the forces of life and the forces of darkness, which extinguish. (Larson 76-77)

[…]

It is the merging of the autobiographical with collective history that becomes visible in such a story. Boltanski’s choice to leave the chords of the lamps exposed as they hang from photograph to photograph in his Chases High School Altar installations may be interpreted, it has been properly suggested by Twyla Hatt in her analysis of Boltanski’s works on mourning, “as a reminder that we are all connected. The public spaces that Boltanski creates allow for new forms of community and togetherness, regardless of the viewers’ interpretation of the piece” (7). It is because of this togetherness that I felt it meaningful to share a related fragment of my mother’s story. […]

* Elèna Mortara taught American Literature at the University of Rome Tor Vergata. She edited the Italian critical edition of Philip Roth’s early work, Romanzi, 1959-1986 (Meridiani Mondadori, 2017).

Top, Altar to the Chases High School (Courtesy of Christian Boltanski and Marian Goodman Gallery).

Above, the class photo taken in Vienna at the Chajes Jüdisches Realgymnasium in 1931.