A Debt to history: Libyan Jews and Italy’s colonial legacy

In 2012, the Jewish-Italian Holocaust survivor Messauda Fadlun received a startling demand from the Italian government. For several years, she had been the recipient of a state pension extended as restitution to those who had suffered Fascist persecution, but the letter, alleging Fadlun’s ineligibility, declared a cessation of payments and ordered the return of all funds already distributed. In total, Fadlun owed the Italian government 76,000 euros (approximately $92,000), and following her death in 2018, the burden has fallen upon her surviving husband.

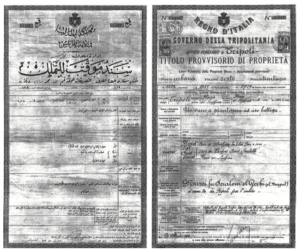

The government’s case rested upon its assertion that Fadlun, who was born in the Libyan city of Benghazi in 1928 and raised in Tripoli, was not yet an Italian citizen at the time of the Fascist regime and thus could not claim restitutive benefits. But Fadlun’s family, which hired counsel and voiced their opposition before the Court of Auditors, pointed out that Libya had already been an Italian colony when the Fascists took power in 1922 and that Fadlun’s “Italian-Libyan” citizenship subjected her to the same antisemitic racial laws that affected Jews in Italy proper. Their appeals, however, came to naught.

The flaws in the Italian government’s case are obvious, and even if the letter of the law truly stood in favor of revocation, the government could scarcely claim the ethical upper hand. But the government’s resolution, though legally dubious and morally untenable, may nonetheless inspire a critical discussion, compelling Italians to consider the legacy of their nation’s colonial enterprises and the responsibility that contemporary Italy bears towards formerly colonized peoples. The case of Messauda Fadlun suggests that, even to those – like many Libyan Jews – who had embraced the culture of their colonizers, some Italians have elected to downplay historical connections and thus to neglect historical debts.

Even before the Italian colonization of their land, many Libyan Jews – especially among the merchant class in Tripoli and Benghazi – had already begun to develop Italian identities, having first acquainted themselves with the language and culture during the late 19th century as a means to facilitate economic relations with Europe. These identities grew stronger and more widespread following the Italian annexation of Libya in 1911. Both Italian state schools and Jewish schools instructed children in the Italian language, cultivating their appreciation of Italian culture and encouraging loyalty to the Italian royal house.

Meanwhile, Jewish adults often worked alongside Italian professionals and even took on roles within the colonial bureaucracy; some came to regard the Italians as agents of progress and modernization, in contrast to the perceived stagnation of their former Ottoman rulers. The active participation of Libyan Jews in Italian public life, however, would not spare them the trials of fascism.

Conditions for Libyan Jews gradually worsened as the National Fascist Party consolidated power in the 1920s and 1930s, and when the regime implemented its discriminatory racial laws in 1938, Libyan Jews suffered much as the Jews in Italy did. Messauda Fadlun’s son, Chief Rabbi of Naples Ariel Finzi, recalls how his mother and her family once traveled to the mountains in order to ease her brother’s respiratory illness, only to be denied lodging because they were Jewish. Lacking other options, the family slept outdoors, and Fadlun’s brother tragically perished. Libyan Jewry endured many such injustices, which eventually came to include imprisonment and forced labor.

Some Jews, in spite of their persecution, still envisioned a future for themselves in Libya under Italian rule, perhaps regarding fascism as a historical anomaly. At the conclusion of the war, however, Italy withdrew its colonial presence in Libya. This retreat coincided with multiple instances of antisemitic rioting, and even those Jews who had yearned for a future in Libya began to look elsewhere.

Thus did the vast majority of Libyan Jews – approximately 90% – make their way to the nascent State of Israel in 1948 and the following years; Messauda Fadlun counted among this wave of immigrants, though she would relocate to Italy upon marrying ten years later.

A thoroughly Italianized minority of Jews remained in Libya after it gained its independence, associating predominantly with the Italians who had remained in the country. These Jews would finally depart in 1967, when antisemitic violence following the Six-Day War made Jewish life in Libya untenable; the majority settled in Italy, establishing themselves primarily in Rome. Members of this population have risen to prominence within religious and secular spheres alike, suggesting that Italy has finally embraced the Libyan Jews who had themselves so often embraced the Italians. The case of Messauda Fadlun, however, suggests otherwise – that Italy more readily claims its former colonial subjects when to do so compels no accountability for historical persecution. Having first betrayed Fadlun decades ago through discrimination, the state has now betrayed her again through revisionism and neglect.

*This piece is part of a series of articles written by students of Muhlenberg College (Pennsylvania, USA) enrolled in a course on the history and culture of Jewish Italy, taught by Dr. Daniel Leisawitz, Assistant Professor of Italian and Director of the Muhlenberg College Italian Studies Program.