The collapse of Kabul and that day we do not remember

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan when they walked into the country’s capital, Kabul. While the international commotion that accompanied the event has retreated, alarming news about attacks on women’s rights and independent media never stopped. Here’s a reflection by social historian of ideas David Bidussa recently published by Pagine. It is a worrying intake and it has never been more of the actuality.

By David Bidussa*

A time of evaluation is opening its doors and I think it would be appropriate to find a way to retrace two scenes: the first scene concerns us in the present, so I will tackle it now. As soon as Kabul fell, there was talk of lists of unmarried women in the hands of the Taliban, women to take possession of. This scene is Afghanistan. What has gone wrong and what have we been pretending to tell each other over the past twenty years? Not only in the United States, but here, too.

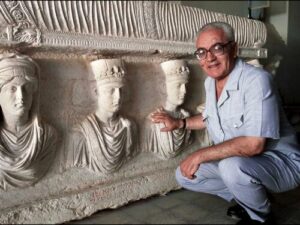

Many blame Biden (and inevitably Obama). Gilles Kepel (Il ritorno del profeta, Feltrinelli 2021) invites us Europeans to make a serious self-examination without dodging any question. There will certainly be time to talk about this, but I would like to focus on the second scene instead. On 18 August 2015 in Palmyra, Khaled al-Asaad, archaeologist and keeper of Palmyra, was tortured, killed, beheaded and his violated body was “shown to the world”. And still, that image did not enter collective memory.

I would like to mention that here. Because in the coming weeks, regardless of the anniversary, which has never entered our public rituality anyway, that scene will perhaps return to speak to our present due to the news that we are receiving from Kabul. I fear that if this happens, many will choose the less problematic side. That is why I insist on reflecting on this second scene.

Let me explain myself. The fact that Daesh kills Khaled al-Asaad is not only a result of some totalitarian dimension pertaining to it. The previous factor matters, of course, but it is not essential. The point is that Daesh chooses to violate Palmyra and display Kaled al-Asaad’s body for a specific purpose.

As a matter of fact, Palmyra is not just a cultural world heritage that fanaticism has attempted to violate and almost completely destroyed. Palmyra is a symbol radically alternative to Daesh and, in a time of sovereignist movements, decidedly disliked and unpleasant to many, even here, where we live.

It is such a symbol in many ways: for its history, for its construction, and for the language circulating in its streets in ancient times: Aramaic, a language which does not belong to any nation, but which thrives on the intertwining and the ability to hold together several languages and types of knowledge, and, along these lines, to create a form of knowledge that functions as a crossroads. Aramaic was not the testimony of compromise, and therefore of renunciation. On the contrary, it was the testimony of “hybridization” conceived as a place where to produce augmented knowledge.

It is such a symbol in many ways: for its history, for its construction, and for the language circulating in its streets in ancient times: Aramaic, a language which does not belong to any nation, but which thrives on the intertwining and the ability to hold together several languages and types of knowledge, and, along these lines, to create a form of knowledge that functions as a crossroads. Aramaic was not the testimony of compromise, and therefore of renunciation. On the contrary, it was the testimony of “hybridization” conceived as a place where to produce augmented knowledge.

This is the reason why Daesh wanted to destroy it. In this respect, the partial destruction of Palmyra and the killing of Khaled al-Asaad are not a repetition of what, for example, took place in March 2001 in Bamiyan, when the Afghan Taliban blew up the statues of Buddha.

The killing of Khaled al-Asaad has a more radical meaning.

Palmyra is not only a place worthy of respect. Nor is Khaled al-Asaad only an industrious intellectual. Palmira is above all a symbol of “crossbred wisdom”. In other words, culture that is built by crossings, overlaps, and hybridizations. We are dealing with a form of culture that is no “daughter of a minor deity”. A culture that is “more”. And Khaled al-Asaad wanted to exalt that trait with his work.

It is important to remember that there are no pure cultures that have never betrayed their original code. Cultures, those which survive over time, are always the result of loans: they give to other ones, but they are above all preserved over time because they assimilate things from other ones.

A living and thriving culture is able to acknowledge that every culture is never equal to itself. A culture is markedly itself if it continually rethinks, modifies, and assumes resources, concepts, and foundations coming from elsewhere. A culture is alive inasmuch as it is a consequence of this process of constant mixing and hybridising, even with those cultures it is in bitter conflict with.

Palmyra was exactly the testimony and memory of this process: a place that produces cultural hybridization over time. The sign of interculture, rather than multiculture. This is why Daesh wanted to destroy it. That date did not enter our civil calendar precisely because of the intercultural nature of Palmyra, seen from the perspective of the nationalist profile that dominates language, even our own one far from Palmyra, in what we call the “free world”.

From top, an explosion in Kabul and Khaled al-Asaad, keeper of Palmyra.

Translation by Gianluca Pace, student at the Secondary School of Modern Languages for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, intern at the newspaper office of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche.