BOOKS – When Great History meets our ordinary lives

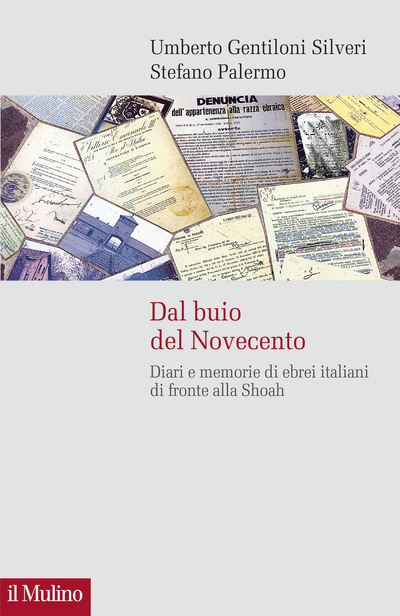

Thirty-nine diaries and memoirs, authored by Italian Jews in the years of anti-Jewish persecutions, come back to us in the book Dal Buio del Novecento (From the 20th Century’s Darkness), published by Il Mulino. Curated by Umberto Gentiloni and Stefano Palermo, the collection offers historical testimonies ranging from the Holocaust to the present day.

Thirty-nine diaries and memoirs, authored by Italian Jews in the years of anti-Jewish persecutions, come back to us in the book Dal Buio del Novecento (From the 20th Century’s Darkness), published by Il Mulino. Curated by Umberto Gentiloni and Stefano Palermo, the collection offers historical testimonies ranging from the Holocaust to the present day.

Preserved by the National Diary Archive in Pieve Santo Stefano, near Arezzo in Tuscany, these texts share a need to express the authors’ experiences, intertwining history and personal stories. They serve as valuable sources for reflecting on the Shoah in Italy thanks to two choices made by the writers. First, they wrote during the fascist and Nazi persecutions, which initially affected the rights of Italian Jews (1938–1943) and later their lives (1943–1945). They captured the reality of those moments while attempting to live their lives, unaware of what would happen later. The second choice is to recall their experiences years later when they can retrace the entire story, knowing how it ends.

Diaries and memoirs are additional pieces that help us to reconstruct the Holocaust. These different forms of testimony help historians and supplement oral sources. They date back to the “era of testimonies,” as defined by Annette Wieviorka, ranging from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. Why does one keep a diary? Why does one feel the need to write down one’s story? “To write, to exist,” write Umberto Gentiloni Silveri and Stefano Palermo in the introduction to the book we read. Writing and telling one’s story is important because the fear of being forgotten is ingrained in the horror of the Holocaust and Nazi camps.

The authors of Dal Buio del Novecento organized these diaries and memories into an itinerary that recounts the events of the Italian Shoah. They highlight important dates and address the protagonists’ emotions. Readers can explore the differences in the diaries’ authors’ daily lives before and after 1938, when racial laws were established; the joy on July 25, 1943, when the Fascist regime collapsed fell; the confusion in September 1943, when Italy was occupied by the Nazis; and the fear of persecution and Italy’s liberation by the Allies on April 25, 1945.

For the survivors, what remained was a sense of relief and the dilemma of not being understood. Emblematic are the words: “Time! To forget! To live!” written in the diary of 15-year-old Fanny Bailey at a time when the rest of her country urged Jews to be patient. “You got lucky. It could have been much worse. You need to be patient…” Fanny Bailey was told. She promptly wrote these words in her diary shortly after the Liberation.

In fact, many Italian Jews were patient. They only started to tell their stories many years later. This was also because many of them had relied on the writer Primo Levi, as Pietro Terracina argued. “Primo Levi represented us all. His was a voice the survivors could relate to. Many of us remained silent because he represented us, and because we were in awe of him, his culture, and his depth. With his sudden passing, we once again felt alone in difficult and sometimes hostile times.” After Levi’s tragic death, many Italian Jews dedicated themselves to sharing their stories. This book aims to honor that effort by sharing the stories of the protagonists as a cautionary tale to never forget.

Translated byRebecca Luna Escobarand revised byFrancesco Gambino, students at the

Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainees in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities — Pagine Ebraiche.