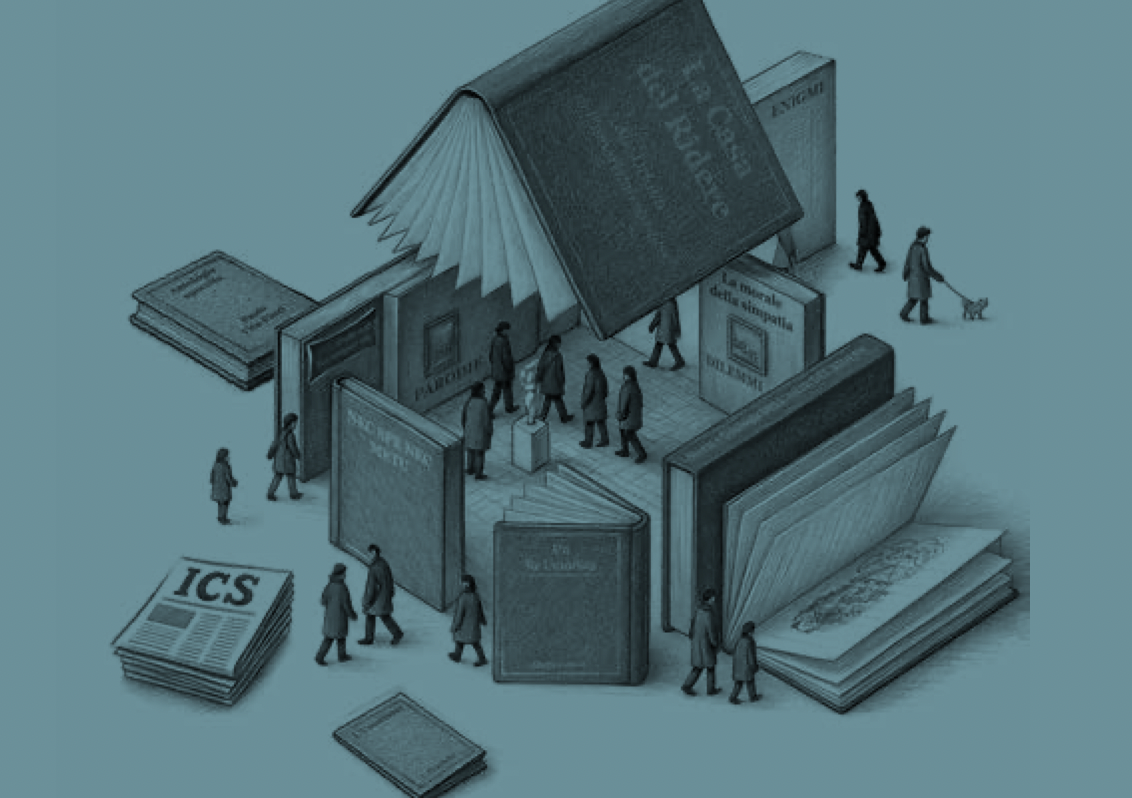

A “House of Laughter” Opens in Bologna, Honoring Massarani, Cantoni, and Formiggini

“If you came here to see Woody Allen, Jerry Lewis, Borat, or Mrs. Maisel, then you’ve come to the wrong exhibition.” This warning opens the La casa del ridere (The House of Laughter) exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Bologna. Curated by father-and-son team Alberto and Emanuele Cavaglion, the show aims to rediscover the roots of a less mainstream form of Jewish humor: Italian humor. The journey is condensed into a few square kilometers, which the curators define as “a small, minimal, rustic land, placed between two confining Padania states, between the Via Emilia and the bends of the River Po.”

This is the land of Angelo Fortunato Formiggini. A publisher from Modena, he took his own life by jumping from the Torre Ghirlandina of his hometown cathedral in 1938 after the promulgation of the racial laws by the Fascist state. The “humorist king” Alberto Cantoni also originated from this area. Born in Pomponesco in 1841, he developed his own specific point of view on Jewish identity in the short story Israele Italiano (Italian Israel).

Tullio Massarani also hailed from that area. Born in Mantua 15 years after Cantoni, he was the first Jew nominated senator by the Italian king. Massarani reviewed two thousand years of humor, starting with the study of the biblical text.

“This exhibition is the realization of an old dream,” explained Alberto Cavaglion, a scholar of Italian Judaism and the author of influential essays on Primo Levi, Italo Svevo, and other figures who shaped the Jewish experience in the 20th century. For years, Cavaglion had hoped to breathe new life into one of Formiggini’s eclectic projects: a “house of laughter,” where different peoples could experience a sense of brotherhood by getting to know each through their “most fun and human characteristics.”

The Cavaglions’ “Geography of Laughter” begins in Poggio Rusco, where Massarani took his first steps in a noble court, and continues through Pomponesco. “It is a place familiar to us in other ways,” they state. The main square was the setting for the remake of the 1952 film based on Giuseppe Guareschi’s book Don Camillo. Years later, in the popular bar, “even Tinto Brass’s Monella danced wildly.”

The exhibition is open until January 11. Its goal is to “comfort the afflicted by giving everyone a chance to forget the ugliness of the world, if only for half an hour.” Once serenity returns, the hope is that a real house of laughter “made of bricks, sober and welcoming, warmed by our smiles will be built to give hope to our restless and frightened souls.” In the meantime, there is “the enormous satisfaction of having worked side by side with one of my sons, who created the illustrations for the panels. This exhibition was born right on our kitchen table.”

Translated by Rebecca Luna Escobar, student at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainee in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities — Pagine Ebraiche.