Racially Persecuted People 70 Years After the Terracini Law

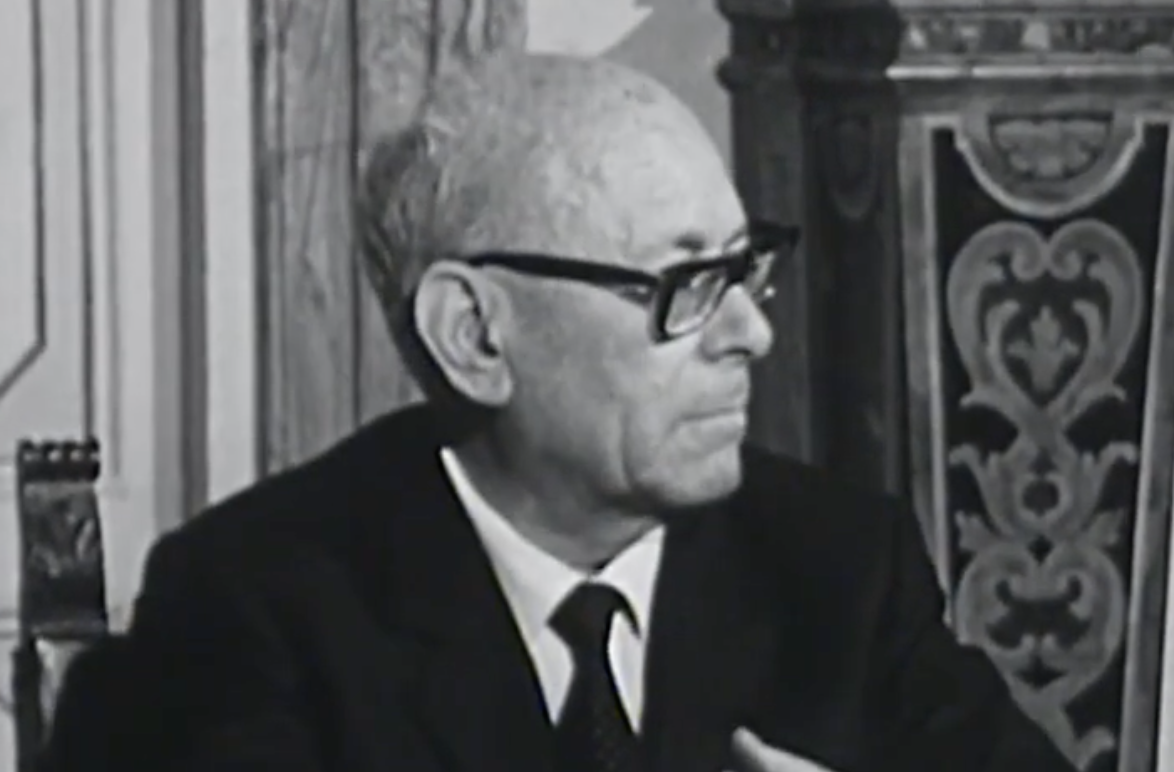

The “Terracini Law” on pensions and restitution for victims of Fascist racial persecution was approved on March 10, 1955. Named after its main proponent, Italian Jewish anti-Fascist Umberto Terracini, the law was an example of restorative justice in a postwar Italy still grappling with democratic reconstruction and the collective repression of past sins. The law had great symbolic and civic value, and was meant to recognize the price paid by those targeted by Fascism for their ideas or Jewish identity, both materially and symbolically. However, seventy years later, the journey toward fully recognition of the rights of the persecuted is incomplete, said Giulio Disegni, the UCEI representative on the Commission for Provisions to Anti-Fascist and Racial Political Persecutees at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Disegni wrote this analysis for Pagine Ebraiche after the commission reconvened in October 2025, following a hiatus of over a year and a half.

From proof of persecution to presumed recognition

A significant step forward was only recently achieved with Law No. 178 of December 31, 2020, which finally eliminated the often-insurmountable burden on applicants to demonstrate the racial persecution they had suffered from.

Persecution is now presumed for all Jews who were in Italy during the racial laws, overcoming a historical injustice that had denied the benefit to many survivors or their heirs for decades.

Applicants are now left with the burden of proving their Jewishness during that period. This is not always an easy task: many Jewish communities no longer have archives from that period or cannot certify the religious affiliation of those who joined only after the war. In these cases, one could easily resort to a rabbinic declaration, but practices are not always uniform across the territory.

Indirect Questions and Disability: The Absurdity of “Able to Work” Eighty-Year-Olds

The chapter on indirect claims, those submitted by the children or surviving spouses of the persecuted, is no less complex. Even today, the law still requires that applicants be “unfit for profitable work” — a concept dating back to the 1950s verified by INPS Medical Verification Commissions. These commissions apply outdated criteria; in some cases, people aged 85 or 90 are deemed “able” and excluded from benefits. Added to this is a further restriction: income cannot exceed €19,500 gross per year, a threshold that effectively makes the benefit inaccessible to many applicants.

The Issue of Rejected Applicants

Another open question concerns those who submitted applications before the 2020 reform. Many applications were rejected in those cases because there was no direct evidence of persecution.

With the new framework presuming persecution of Jews, it would be logical to reexamine those cases. However, the commission does not always agree, claiming that a final decision has been made on previous applications unless an appeal has been filed with the Court of Auditors.

This formalistic interpretation contradicts the spirit of the new law, leaving many applicants or their heirs in a state of injustice.

The Jews of Libya Are Still Waiting

The situation of Libyan Jews remains unresolved amid racial persecution. Many of them were victims of discrimination, but did not hold full Italian citizenship; they held only a so-called “small citizenship.” This status excludes them from the benefits provided by the Terracini Law, a legal anomaly that has long required clear and decisive political intervention.

A Memory that Must not Be Archived

Seventy years after its approval, the law championed by Umberto Terracini remains a milestone in the history of the Italian Republic. However, amid bureaucratic constraints and restrictive interpretations, the law’s original spirit — recognizing the dignity and memory of those affected by racial and political hatred — is at risk of being lost. Therefore, the Commission’s meeting at the Ministry of Economy and Finance, attended by representatives of institutions, the National Association of Politically Persecuted Anti-Fascist Italians (ANPPIA), and UCEI, represented not only an administrative act but also a moment of civic reflection.

Memory is not just reflection; it is also a commitment to making justice accessible, concrete, and alive.

As Terracini recalled, freedom is not a gift but a duty—that of remembering and making reparation. The Republic cannot be considered complete until it has morally and materially compensated those harmed for believing in freedom and equality. Seventy years later, that promise remains unfulfilled. Seventy years after it was enacted, that duty remains relevant.

Giulio Disegni

Translated by Alessia Tivan and revised by Matilde Bortolussi, students at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainees in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche.