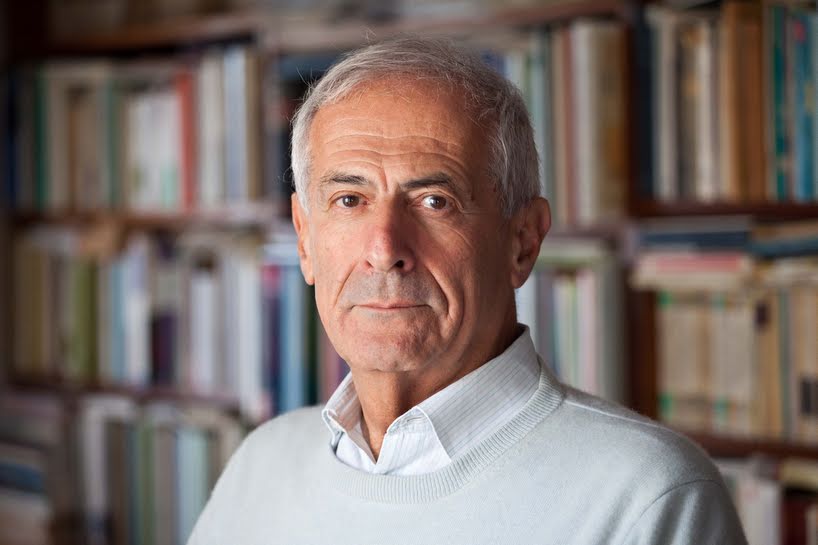

Della Pergola: “The Lesson of Memory Has Not Been Internalized”

Twenty-six years have passed since the establishment of Holocaust Remembrance Day. The Italian-Israeli demographer and antisemitism scholar Sergio Della Pergola does not hide his enormous sense of disappointment in the face of Western society’s failure to process what happened. “It was hoped that this would be an established fact. Instead, we discover that it is not at all,” he said.

The Shoah, he told Pagine Ebraiche, has not become a stable civic heritage. It remains fragile and reversible, exposed to continuous distortions. This leads to a provocative statement that reflects his severe judgment: “Jews should boycott Holocaust Remembrance Day.”

This is not because that memory should fade. But rather, it is not the Jews who should be reminded of the Shoah. “Holocaust Remembrance Day is not a day to remember the Jews, but the perpetrators and the indifferent and their descendants,” he explained. “The Jews suffered the Shoah and have never forgotten it. The problem concerns the majority of society and its inability to come to terms with its historical responsibilities.”

According to Della Pergola, a professor emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an influential representative of Italkim (the Italians in Israel), October 7, 2023, marked a turning point. Not because it generated antisemitism, but because it shattered the illusion that certain achievements were now solidified. “It was thought that certain barriers could no longer be broken down,” he noted. “Instead, everything has been put back into question: the discourse about Jews, Israel, and the idea of Jewish estrangement.” The latter, he added, is an accusation that tends to reemerge cyclically. Perhaps, he suggested, “it has never truly been overcome. And perhaps it never will be.”

The most recent data measure this regression. Della Pergola recalled that, “According to a survey by sociologist Renato Mannheimer, about 14 percent of Italians believe that Jews should be expelled from the country.” Peaks are found at the extremes of the political spectrum.”

“Even more telling is another figure: Almost half of the interviewees attribute responsibility for ‘Nazi-type’ crimes in Gaza to Israel.” For Della Pergola, these numbers do not indicate absolute novelty but rather the persistence of an anti-Jewish “hard core” that has changed its language and ideological positioning over the decades without losing intensity.

For this reason, he concluded that speaking of memory without questioning the society that celebrates it risks transforming memory into an empty ritual. “The problem does not belong to the Jews,” he insisted. “It pertains to the society looking at them.”

In this context, he added that the current Italian debate on the antisemitism bill seems “surreal.” Rather than addressing the growth of anti-Jewish hatred, the debate gets caught up in terminological disputes and hypothetical fears. He remarked that laws are not sufficient on their own. However, they do serve to mark a boundary. “Today, that boundary is too often bypassed or openly denied,” he said.

Turning to the Italian Jewish context, Della Pergola offered one final observation about the Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI). After elections were held on December 14, 2024, the organization has yet to appoint a new president and board.

“From Israel, observing the future of the representative body of the Italian community, one would expect a rapid and determined effort to rediscover lost unity and fight together against a common enemy.” This hope, he concluded, translates into a concrete request: “To quickly establish an organizational structure capable of addressing these problems.”

Daniel Reichel

Translated by Matilde Bortolussi and revised by Alessia Tivan, students at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainees in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche