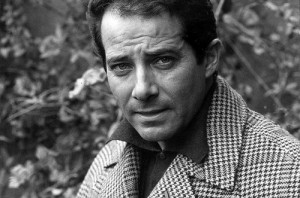

ITALIAN PORTRAITS Gillo Pontecorvo, a Passion for Telling Stories

Gillo Pontecorvo did not go to synagogue every Friday, or observe all the holidays. He was not a “perfect Jew,” but he was an innovative one. Gillo was born in 1919 in Pisa, Italy, into a large Jewish family, with nine brothers and sisters. Instead of following family traditions and pursuing an education in the sciences like all of his brothers, Gillo rebelled and decided to follow his love of journalism. Although he began his studies at university, he quickly realized that it was not for him. He felt uncomfortable there because of his Anti-fascist beliefs, and was afraid that scientific studies would hinder his passion for journalism.

After the passage of the Italian Racial Laws in 1938, Pontecorvo left for Paris to pursue a career in journalism. There he realized something that would change the rest of his career: pictures speak louder than words—he then transformed his career to a focus on visuals: photojournalism.

When Pontecorvo returned to Italy, the war was raging. As an Anti-fascist, he became an active member of the Communist Party. He joined the Resistance Movement, worked with the underground Communist news archives and also became the leader of the Communist youth association.

After the war, Pontecorvo’s career took another turn when he saw Roberto Rossellini’s 1946 film Paisà. Profoundly struck by the neo-realist masterpiece, Pontecorvo perceived the impact that political film can have on the public. In the early 1950s, Pontecorvo began making documentaries with a 16mm camera that he bought himself. In these documentaries he displayed his political beliefs and social concerns front and center, investigating the lives of everyday Italian workers.

In 1956, Pontecorvo began his fiction filmmaking career. Although his attachment to ritual Judaism may have been tenuous throughout the majority of his life, Pontecorvo’s second full-length movie, Kapò (1960), focused on the Shoah: the most devastating event in Jewish history, and not a common subject for feature films at the time. This movie, revolves around the character of Edith, a naïve young French-Jewish girl, who is deported to a concentration camp, and is forced to take up the identity of an already deceased political prisoner in order to survive. As time progresses, she becomes a kapo—a prisoner functionary who is in charge of the other prisoners, and therefore, becomes necessarily complicit in their oppression, sinking ever deeper into the murky ethical territory that Primo Levi labeled as the “grey zone.” She eventually tries to help the prisoners escape, and is killed in the attempt. The grainy black and white aesthetic of the film, along with Pontecorvo’s attention to characters’ faces, creates a tense and somber mood throughout. Pontecorvo also uses documentary clips with the combination of his original shots to give the movie a more chilling, realistic feel.

Pontecorvo’s next film became his most critically celebrated: The Battle of Algiers (1966). A movie about the Algerian War, fought between Algerian guerillas and the French army, Battle of Algiers was shot on location in a striking documentary style. Its release led to furious critical and political disputes, and was even banned from release in France for five years. It has since been hailed a classic of cinéma vérité-style filmmaking. Battle of Algiers and Kapò both contribute to Gillo Pontecorvo’s legacy; his passion for politics, cinema and storytelling have lead to his underappreciated achievements. Although he was not a prolific film maker, his memory will live surely on thanks to his dedication to political filmmaking that forces viewers to ask tough ethical questions. As Pontecorvo stated in a 1991 interview, “I am like an impotent man, who can make love only to a woman who is completely right for him. I can only make a movie in which I am totally in love.”

*Lindsay Shedlin is a student at Muhlenberg College (Allentown, Pennsylvania, USA).