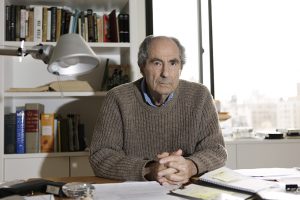

CULTURE Philip Roth, The Last Interview

Two years ago on December 21, 2017, Italian scholar Elèna Mortara walked through Manhattan’s Upper West Side on her way to her appointment for a historic interview with American legendary writer Philip Roth.

The result of that very special meeting, which apparently marked the last interview granted by Roth was published in the journal of the Philip Roth Society, the “Philip Roth Studies.”

“Up on the twelfth floor, near the threshold, just outside his open door, there is Philip Roth, welcoming me. When I enter, I am flooded with the light of the bright and spacious living room, with large balcony-windows over the opposite wall open to the sight of the city. Roth is wearing a slate-blue shirt and brown wool trousers. We sit in this light-flooded space, with a low table filled with books next to us, and start our conversation. It’s a friendly conversation, moving from memories of his experience in Rome as a young man to family recollections, from his encounters with other writers to reflections on his books. There are moments of great laughter and sometimes surprising discoveries to be made in this conversation. Roth is not only welcoming, but also looks in great shape. “I’m happy,” he admits with all simplicity, when I ask him how he feels, now that he has just published a new splendid collection of essays (Why Write?, 2017) in the United States,” Mortara wrote.

A Professor of American Literature at the University of Tor Vergata in Rome, Mortara is the editor of the first volume of Roth’s works in the most in the most prestigious Italian literary series, Meridiani Mondadori.

At the time of the interview, the first volume had been published only two months before.

Among the topics they covered, were Kafka’s influence on Roth’s work, as well as his Jewish roots.

“The Jewish families, they had a right to leave between 1880 and 1900. And the first generation struggled, but their children, who had a step up, who were more middle class, formed these family associations. They were very common among Jews. They were kind of welfare societies, they would loan money for burials, if someone was sick, they had a scholarship fund for kids going to college, who didn’t happen to have money. And then there was great family feeling among them. I, as a little child, I loved going; when I was a little one, I loved going. I think by the time this one was taken, I was too sophisticated!” Roth told Mortara showing her a picture —with about 150 people sitting at long tables in an elegant dining room, all relatives of his.

“You know, my parents, they were very important to me, because they were so good and raised my brother and me with such warmth and love. But also the community where I grew up, that neighborhood, was a big neighborhood, Jewish neighborhood, was like a larger parent. Because they were all Jews, there were a few Gentile families, but not very many. I guess I was speaking to one of my old high-school friends on the phone, he lives in Florida, and we speak once in a while, and he said to me about Weequahic, our neighborhood: ‘It was so safe,’ he said, ‘we felt so safe.’ And we really felt so safe,” he added.

“I feel that for you Jewishness has been very important, not Judaism as a system of thought, as a religion, but Jewishness, the experience of being a Jew,” Mortara remarked.

“Yes, ethnic Judaism we might say. Sure, because I was always aware of myself as a Jew, though I was never observant. I was bar-mitzvah, that was the last time I went to a synagogue. The historical predicament of Jews became clear to me very early. So I always was aware of it. As far as the choices of my people in my books, I wrote about them because I knew about them. I was interested in Jews, I was interested in these people I knew, they were Jews, you know,” he answered.

The two also discussed Italy’s presence in Roth’s books.

“Is Italy present in my books?” Roth remarked at first. “I don’t even notice it! Can you tell me in which books?”

After Mortara pointed out some of the scenes, the writer recalled his first time in the Peninsula.

“The first time I went to Europe I was in Paris, and then I hitchhiked down to Florence. And I just did the things that a young fellow—I was twenty-five—a young fellow would do. I saw everything, you know, studiously saw everything. But that’s what made me want to go back in 1959, that I wanted to see more of Italy. You know, at that time in America it was no longer Paris that was the place to go to. Rome was the place to go to,” he said.

“It is moving for me who was there to listen again to Roth’s voice, enjoying the marvel of the almost three hours I spent with him in intense, exciting conversation,” Mortara concluded in the piece published in the journal. “Not many days after our meeting, the New York Times of January 16, 2018, published an interview with him by Charles McGrath, which had actually taken place, as specified at the start of the article, a few weeks before our meeting,” she continued.

“At the end of that day, sometime after sunset, while I was leaving, Roth showed me the satirical drawings hanging next to the front door at the entrance of his apartment. They were the famous drawings by Philip Guston inspired by his novel The Breast: his grotesquely self-ironical version of Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis, telling of professor David Kepesh, who, obsessed by sex, finds himself ‘inexplicably’ transformed into a gigantic breast. With a tone between seriousness and playfulness he remarked, with some pride: ‘With this novel, I anticipated the transgender culture!’ He knew he had been revolutionary and not always understood,” she concluded. “Upon my leaving, we hugged each other, next to the door. In parting from him—he who still looked so tall and straight and was so kindly warm to me—I thought that ours was a friendly and promising goodbye, un arrivederci, as we say in Italian; instead, it was a final adieu, un addio.”

*Portrait by Giorgio Albertini.