The man who saved Yiddish literature

It was defined as one of the biggest efforts of cultural rescue in Jewish history. It was Aaron Lansky, a then-young student of Yiddish language and literature, who set it up in the 70s. Failing to find books in Yiddish to read, Lansky began to check around by asking institutions and private citizens if they had some to borrow or donate. The response was tremendous, given that many books would otherwise have gone to the shredder or ended up in landfills.

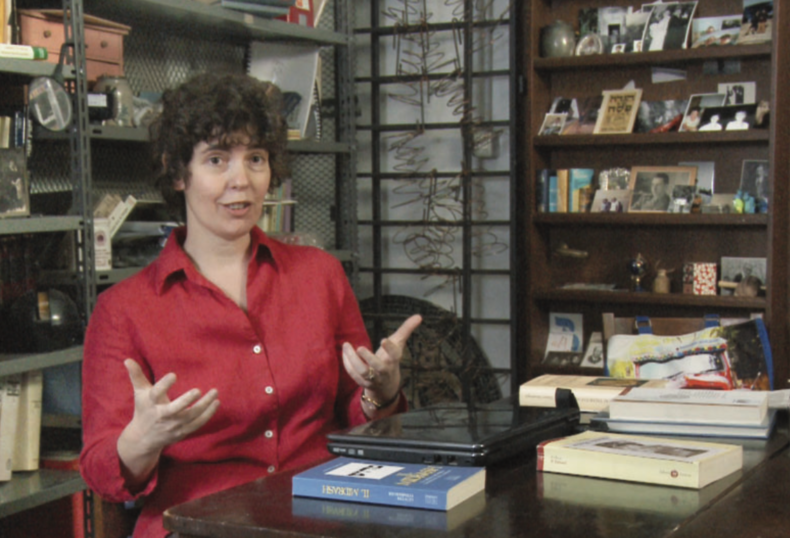

“Lansky’s undertaking has become a real and incredible one. He tells it in a wonderful book of several years ago now, which is titled Outwitting History: How a Young Man Rescued a Million Books and Saved a Vanishing Civilisation” says Anna Linda Callow, a translator and teacher of Yiddish and Jewish. “Thanks to him and the center he established in Massachusetts, the reading in Yiddish was the world’s first to be digitalized. That is why you can choose among a large amount of uncopyrighted material that’s available simply going to the National Yiddish Book Center website”.

“Lansky’s undertaking has become a real and incredible one. He tells it in a wonderful book of several years ago now, which is titled Outwitting History: How a Young Man Rescued a Million Books and Saved a Vanishing Civilisation” says Anna Linda Callow, a translator and teacher of Yiddish and Jewish. “Thanks to him and the center he established in Massachusetts, the reading in Yiddish was the world’s first to be digitalized. That is why you can choose among a large amount of uncopyrighted material that’s available simply going to the National Yiddish Book Center website”.

As Lansky tells in his book, we are talking about a rescue and restoration work which began by chance. “At the beginning he needs the books just to improve the language and the attempt to recover them is disastrous. For example, he goes to a religious books salesman who kicks him out of his shop because he doesn’t want to sell him any text in Yiddish, since he thinks they do not comply with the Jewish laws.” Then the word about his research gets out, and many approach him to get rid of pages and pages with which nobody knows what to do. “It’s the second generation who can’t read the language anymore and wants to dispose of piles of books it considers useless. So, Lansky starts having them sent everywhere, even to his girlfriend’s house, who threatens to leave him. Meanwhile, he works on the idea of opening a center, having understood that if he’s not the one who cares about that, nobody will. Then an entire heritage would end up in a landfill.”

Thus began the attempt to find and raise funds for the center. “Again, initially the answer was No sympathy. The Jewish institutions respond: Who cares about them? Who wants them? Then, in addition to a small university funding, he gains support from all those who still care about their Yiddish books, like the poor elderly who came in the US decades earlier and did whatever it took to buy those pages. Now they help him out as best as they can, with micro donations to cut their losses. It’s a very touching story.” “But it is kind of compelling, too” Callow adds. “There are stories of how he rushes from Massachusetts to NY to rescue some books that are at risk due to the rain. Or stories of how he intervenes while a building is being demolished where the older communist club had its seat. And under the pieces of plaster there’s an entire library. Or again, how he must smuggle the books from Canada because of an intricate set of laws. It’s a funny book that tells the story of a very important place for the preservation of the Jewish culture”.

Translation by Sofia Busatto, revised by Valentina Megera, students at the Secondary School of Modern Languages for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, interns at the newspaper office of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche.