“The stolen books of our identity”, interview with historian Serena Di Nepi

By Daniela Gross

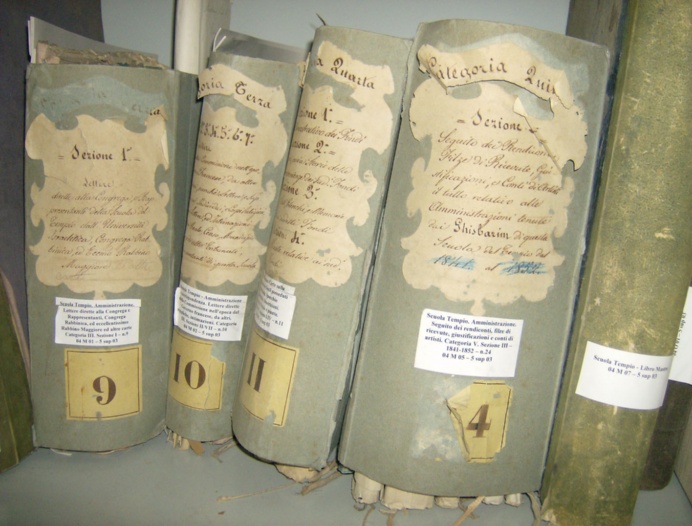

The Community’s centuries-old collection is loaded onto a special train bound for Germany two days before the Jews of Rome are deported. An immense heritage of history, knowledge and tradition is thus snatched from Italian Judaism – seven thousand texts dating back to the late Middle Ages and including codices, incunabula and books made by extraordinary printers such as the Soncino, Bomberg, Bragadin and Giustiniani between the 16th and 18th centuries. There were 25 examples hidden elsewhere and three thousand volumes, mostly prayer books printed at the end of the 19th century, which the Nazis deemed of little interest.

What happened after the departure of the train is, however, shrouded in mystery. After the war, thanks to the work of the Italian Restitution Mission headed by Rodolfo Siviero, the texts from the library of the Rabbinical College stolen a few months later were found and returned. Despite the research and efforts of the various institutions, the Community’s bibliographic heritage seems to have vanished into thin air. As historian Serena Di Nepi – who in the catalogue of the exhibition Arte liberata reconstructs the raid and its impact in a fine essay – explains to Pagine Ebraiche, two questions still weigh heavily on that event: What books were stolen? And what happened to them?

What happened after the departure of the train is, however, shrouded in mystery. After the war, thanks to the work of the Italian Restitution Mission headed by Rodolfo Siviero, the texts from the library of the Rabbinical College stolen a few months later were found and returned. Despite the research and efforts of the various institutions, the Community’s bibliographic heritage seems to have vanished into thin air. As historian Serena Di Nepi – who in the catalogue of the exhibition Arte liberata reconstructs the raid and its impact in a fine essay – explains to Pagine Ebraiche, two questions still weigh heavily on that event: What books were stolen? And what happened to them?

Even today, it is still not known exactly what was included in the collection. For what reason?

The reasons are historical. Starting with the first Inquisition Index, which banned or expurgated many Jewish texts, Jews avoided cataloguing their libraries in order to protect them from censorship. Searches in the ghettos were as frequent as the seizure of books. Therefore, summaries from earlier periods were used for study and texts are imported from the Ottoman Levant or Amsterdam. In later times, Emancipation entailed a loss of Jewish culture and books therefore ended up relegated to some office or rabbi’s room. It was not until the 1930s and a generation of great scholars such as Attilio Milano, Umberto Cassuto or Isaiah Sonne that libraries returned to the centre of attention.

It was Sonne himself who, before being expelled by the fascist regime, undertook an initial investigation of Italian Jewish libraries.

It was an operation of great importance from which one could see both the general structure and the exceptional nature of the Jewish Library of Rome, one of the largest in Europe at the time. We are talking about a collection of 10-12 thousand volumes that dates back to the 2nd century. It was developed from the collections of the ritual confraternities and over time was enriched with extraordinary texts, including 16th century codices – some of which have been saved and are now on display at the Quirinal Palace in Rome – Levantine prints and books intended for ritual or study.

The Nazi raid does not therefore fall at random.

Quite the contrary. The commando in charge of the raid is composed of experts: Scholars of the highest order, with enormous bibliographic expertise, who know Hebrew. They know all too well what they are doing and they are going for it.

The fate of those books has never been clarified. What are the most credible hypotheses?

What is known is that the train on which they were loaded left and was not bombed. However, it is not known whether it reached its destination or what it was. According to experts, no volume with the markings of the Library of the Jewish Community of Rome would have entered the always flourishing Jewish antiquarian market. One possibility is that at the end of the war the books followed the Red Army on its return to Russia and are now in the territories of the former Soviet Union. Another is that they are all in some basement or private property, probably in Eastern Europe.

Was enough done to find them?

Over the years, the State and the forces of law and order have made every attempt: I do not believe that anything more can be done.

“The books of the Jews of Rome told,” – as we read in your essay – “by the mere fact of having survived until 14 October 1943, the two-thousand-year-old culture of this community, of its growth and resistance alongside the majority society and in spite of persecution”. What does this loss mean for the Jewish Community of Rome and more generally for Italian Judaism?

It is an immeasurable damage for the whole of Italy, from which an incomparable heritage and a fundamental piece of its history has been taken away. And it is a searing wound for Italian Judaism. Memory has so far focused, as it should, on the loss of human lives: the Holocaust is a mourning that is still alive in Jewish families. The plundering of the books, however, is beginning to find a place in the collective memory, even if it is difficult to fully realise what that loss means. Those books recounted centuries of study, knowledge, and interaction. They are irreplaceable pages that could rewrite many glimpses of Jewish history.

Translated by Maria Cianciuolo and revised by Onda Carofiglio, students at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, interns at the newspaper office of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche