How Italy protected its art from the Nazis, saved masterpieces in display in Rome

Paintings, sculptures, jewelry, and precious artifacts. As the war has been ravaging Ukraine, the tragedy of lost lives and devastations is being accompanied by the systematic plundering of the country’s artistic and cultural heritage, in the name of its so-called “protection”. According to international art experts, the looting ongoing in Russian-occupied areas may be the biggest art theft since the Nazis pillaged Europe during WWII. Back then as now, it is the culture, pride, and identity of a nation that comes under attack. And is a heartbreaking offense, as evidenced by the exhibition ” Arte Libera. Masterpieces saved from war” set up in the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome.

Curated by Luigi Gallo and Raffaella Morselli, the exhibition (until 10 April) offers an extraordinary glance at a hundred masterpieces saved during the Second World War together with many documents, images, and recordings brought together thanks to the collaboration of over forty museums and institutes.

It is a compelling account of a dramatic period for Italy and at the same time a tribute to those who, despite the risks, then took the path of courage and in the name of the common interest claimed the universal value of the Fine arts administration, often forcibly retired after refusing to join the Republic of Salò – which amid the conflict, with the help of art historians and representatives of the Vatican hierarchies, have become the protagonists of a great undertaking to safeguard Italian artistic and cultural heritage.

Among them were Giulio Carlo Argan, Palma Bucarelli, Emilio Lavagnino, Vincenzo Moschini, Pasquale Rotondi, Fernanda Wittgens, Noemi Gabrielli, Aldo de Rinaldis, Bruno Molajoli, Francesco Arcangeli, Jole Bovio and Rodolfo Siviero, secret agent and future plenipotentiary minister in charge of restitution. Men and women who, without weapons and with limited means, became aware of the threat hanging over Italian art collections and took sides to prevent it.

“It is an exhibition of stories. Stories of women, of men, of works of art, protected, saved, lost and recovered”, explains Mario De Simoni, chairman of Scuderie del Quirinale. “Their heroic deeds are an example of patriotism and sense of duty, testifying the effectiveness of the action of an entire generation of state officials who saved the immense Italian cultural heritage, offering it to subsequent generations”.

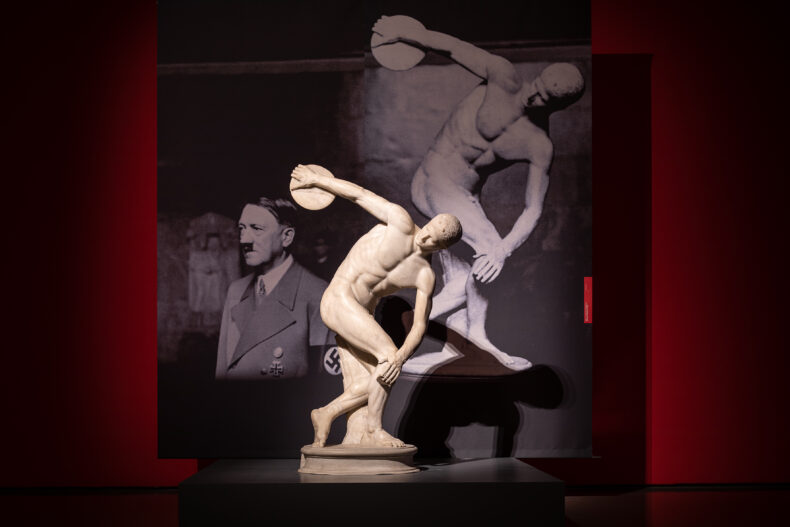

The exhibition starts from the alteration suffered by the art market in the aftermath of the signing of the Rome-Berlin axis (1936). To indulge the collecting cravings of Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring, the Fascist hierarchs favored allowing the sale of important works of art, even under constraint. Among the most famous, is the Lancellotti Discobolo (constrained since 1909), a Roman copy of the famous bronze by Mirone – one of the highlights of the exhibition.

In 1039, Hitler’s invasion of Poland marks a turning point for Italian artistic patrimony. The Minister of Education Giuseppe Bottai set in motion the operations to secure the cultural heritage, with the consequent elaboration of the plan to move works of art. From here a complex and dramatic story unfolds, that sees officials inventorying and hiding cultural assets in Lazio, Tuscany, Naples, Emilia, and northern Italy, thanks to the commitment of female curators such as Fernanda Wittgens, the first woman to head the Pinacoteca of Brera, Palma Bucarelli, Noemi Gabrielli, Jole Bovio, and others, as well as the looting of the Jewish Library in Rome.

Among the key figures in this section is Pasquale Rotondi, the young superintendent of the Marche who was commissioned to set up a national depository and rescued masterpieces from Venice, Milan, Urbino, and Rome in the deposits of Sassocorvaro and Carpegna, totaling about ten thousand works in his custody.

The Nazi looting does not spare the Jewish Community of Rome. The invaluable collections of the Rabbinical College and the Jewish Library of the Community are shipped to Germany. The magnificent ritual objects of the Community, to which the exhibition dedicated a beautiful section, are instead brought to safety by a group of braves thanks to a series of secret deliveries and will be recovered after the Liberation.

The end of the war marks the start of missions for the recovery and preservation of stolen works. Italian officials are joined by men from the ‘Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program (MFAA), a task force made up of art professionals from thirteen different countries and organised by the Allies during the Second World War to protect cultural property and works of art in war zones.

With the end of the war, the commitment to returning stolen Nazi property so begins. Over six thousand works were found to date, but for many others, the search is still on. In the meantime, at Europe’s borders artistic heritage has become again a painful battlefield.

Above, the Discobolus Lancellotti, a Roman copy of the famous bronze by Mirone and one of the exhibition highlights.