ART – Jewish-Italian pianist Francesco Lotoro brings lost music of the Shoah back to the world

For the past three decades, Italian composer and pianist Francesco Lotoro has been on a mission to rescue music pieces composed in concentration, labor and POW camps in Germany and elsewhere between 1933 and 1953. He documents his findings in The Lost music of the Holocaust: Bringing the music of the camps to the ears of the world at last (Headline, 341 pages), which pieces together the human stories of those who wrote and performed while imprisoned, shining a light on the extraordinary role art and beauty played in that darkness.

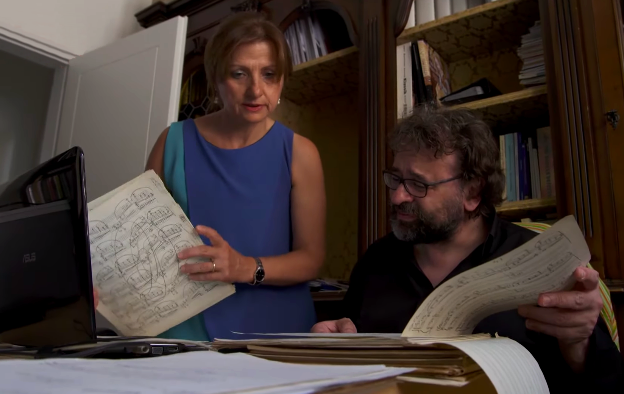

First published in Italy in 2022 by Feltrinelli under the title Un canto salverà il mondo, this book marks his debut in the English-language publishing market. It details Lotoro’s unwavering commitment to recovering, performing, and, in some cases, completing songs, symphonies, and operas composed in the camps. Since 1991, traveling from Italy to more than a dozen countries, he visited concentration camps, searched through archives and bookshops, and interviewed Holocaust survivors and their descendants. He discovered over 8,000 unpublished works of music, 10,000 documents (microfilms, diaries, notebooks, and recordings on phonographic recordings), as well many survivors who before deportation had been trained musicians and composers.

The findings captured in the book are remarkable and historically relevant. He tracked down musical pieces of different genres, from symphony operas to folk songs to gipsy melodies. Many were scribbled down on whatever material the musician had available. Many were in code to avoid being discovered by camp guards. Scores were sewn into coat linings, instruments hidden in suitcases; sheet music stashed among dirty laundry. Making Lotoro’s project even more poignant, many of the musicians were murdered without knowing that their music would one day be heard by the world.

The English book’s title highlights the central role of the Holocaust in concentrationary music. At the same time, this edition emphasizes the musical production in the gulag, the system of forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. These compositions should not be considered a mere appendix to the music created in the lager camps, Lotoro explained in an interview with the Italian daily Corriere della Sera.

“Gulag camps were operating since 1919 in the Solovki islands and involved the deportation, imprisonment and physical destruction of the Mensheviks, dissidents and victims of Stalin purges, through a system of human annihilation later copied by the Nazis.”

The word ‘Holocaust’

Considering these implications, the word Holocaust commonly used in English to designate the genocide of European Jews during World War II does not render justice to what happened. “This expression links together two Greek words, translating metaphorically the animal sacrifices burned in ancient times at the Temple in Jerusalem. Elie Wiesel gave literary support to this term, which deeply differs from the Hebrew word Shoah, meaning destruction. None of us Jews offered themselves as Holocaust to the Germans. Therefore, the world Holocaust depicts a reality very dissimilar from what went on in the camps. It is a literary image for a humanitarian catastrophe.”

It is overwhelming that, despite their deep suffering, men and women still felt the need to create art. As a matter of fact, the explosion of creativity in the camps, writes Lotoro “was an individual and collective strategy of survival.” “Why was it so important making and writing music in the camps? Possibly, the best answer is that of Emile Goue, a brilliant French composer, and prisoner of war, deceased a year after the Liberation for an illness contracted in the camp: ‘Music was neither an entertainment or a game but the expression of our inner life. We were making music very seriously, not ironically. It was impossible to do great things without conviction, and the conviction the artist must bring to his work is nothing other than to believe in the necessity of what he writes.”

Lotoro’s findings will converge in a monumental archive located in the “Citadel of Concentration Camp Music.” The project is currently being developed under his initiative in Barletta, a city in southeastern Italy by the Adriatic Sea, where Mr. Lotoro lives and was born in 1964. The citadel is to include a museum, a library and a theater on the two-acre site of an abandoned brandy distillery.

In 2020, his commitment to preserve concentration camp music from oblivion was honored by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre and was the subject of a documentary by CBS The Lost Music, which was aired twice after the popular tv transmission “60 Minutes” and won a nomination to the Emmy awards.

“For Jews, remembrance is a mitzvah. So, I am doing my duty,” Mr. Lotoro explained at the time. Giving life to music created in the concentration camps, in the harshest of conditions, is not only a testament to the resilience and endless creativity of human mind, but a unique way to help future generations to understand.