JEWISH JOURNALISM – A historic journey from Verona to Turin

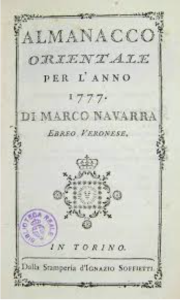

Marco Navarra, a Jewish scholar from Verona who moved to Turin in the late 18th century, is an “illustrious unknown,” says historian Asher Salah. Yet, according to Salah, a professor at the Bezalel Academy of Jerusalem, Navarra played a pioneering role in Italian Jewish history. His Almanacco Orientale (Oriental Almanac) represents an early form of Jewish journalism in Italy. “Contrary to popular belief, almanacs were often more than just calendars listing holidays,” Salah explained. Navarra’s publication, written in Italian between 1760 and 1776, included political news, diplomatic commentary, and cultural essays, catering to a broad, mixed Jewish and Christian audience.

Marco Navarra, a Jewish scholar from Verona who moved to Turin in the late 18th century, is an “illustrious unknown,” says historian Asher Salah. Yet, according to Salah, a professor at the Bezalel Academy of Jerusalem, Navarra played a pioneering role in Italian Jewish history. His Almanacco Orientale (Oriental Almanac) represents an early form of Jewish journalism in Italy. “Contrary to popular belief, almanacs were often more than just calendars listing holidays,” Salah explained. Navarra’s publication, written in Italian between 1760 and 1776, included political news, diplomatic commentary, and cultural essays, catering to a broad, mixed Jewish and Christian audience.

Salah discussed Navarra’s work at the conference “Turin 1424-2024: Six Hundred Years of Jewish Presence” organized by the Turin Jewish community. Although it represents a small chapter in the larger 600-year history of Jews in Turin, the journey offers insight into the social and cultural environment they inhabited, such as their relationship with the House of Savoy.

Navarra published his almanacs through the Royal Press, suggesting institutional support. Salah noted that this support was part of the Savoys’ broader effort to reform their conservative policies and embrace the intellectual influences of the French Enlightenment. The Kingdom of Sardinia was trying to modernize, adopting the principles of free trade inspired by French economic thought, creating fertile ground for Navarra’s work.

Although it hinted at an opening toward the Jewish world, full Emancipation under the Savoy rule was still far off, only arriving in 1848. “It’s no coincidence that Navarra wasn’t a native of Turin,” Salah explains. “The local Jewish community didn’t yet have the capacity for such a cultural initiative, as they were still heavily marginalized, often limited to small trades.”

Navarra, on the other hand, was an outsider with influential connections among intellectuals and rabbis in Veneto. He likely arrived in Turin through his association with another Veronese, Lazzaro Basevi, the first Jewish printer in Piedmont.

Published annually, Almanacco Orientale featured issues of about 200-250 pages, covering general information and international news, including discussions on colonialism and the slave trade. Local Piedmontese topics were likely omitted to avoid censorship. The title “Orientale” can be understood indirectly from another of Navarra’s works, a fictional letter collection where he, as a Jew, portrayed himself as a bridge between the East (the Levant) and Europe. For Navarra, Jews symbolized a link between the two shores of the Mediterranean.