BOOKS – Light and coexistence: The story of an Oleh Hadash

In the late 1960s, Jack Stroumsa, director of the Jerusalem Municipality’s Public Lighting Department, met a young Italian engineer named Gianfranco Yohanan Di Segni. Both were olim hadashim – new immigrants to Israel. Born in Rome in 1941, Di Segni and his family had escaped the Shoah under the protection of a convent of nuns. After the war, he earned a degree in electrical engineering and later moved to Jerusalem with his wife Viviana, inspired by the Zionist dream. Stroumsa, born in Thessaloniki in 1913, was also an electrical engineer and a survivor of Auschwitz and the death marches. Like Yohanan, he emigrated to Israel immediately after the Six Day War.

In the late 1960s, Jack Stroumsa, director of the Jerusalem Municipality’s Public Lighting Department, met a young Italian engineer named Gianfranco Yohanan Di Segni. Both were olim hadashim – new immigrants to Israel. Born in Rome in 1941, Di Segni and his family had escaped the Shoah under the protection of a convent of nuns. After the war, he earned a degree in electrical engineering and later moved to Jerusalem with his wife Viviana, inspired by the Zionist dream. Stroumsa, born in Thessaloniki in 1913, was also an electrical engineer and a survivor of Auschwitz and the death marches. Like Yohanan, he emigrated to Israel immediately after the Six Day War.

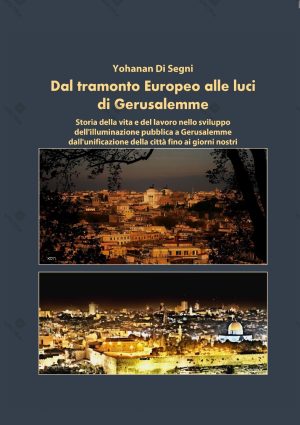

In the Jewish state, the paths of these two men intertwined – a small but poignant example of a life shaped by the tragedy of the Shoah and yet projected into the future. There was a lot to build at the time, and Stroumsa was tasked with maintaining the city’s entire public lighting infrastructure. While assembling a team for the job, he asked Di Segni if he would like to be part of it. “It’s a special job, maintaining and caring for the lighting of the whole city,” he told the young Di Segni over an Italian coffee. “With you, I want to transform Jerusalem from a dark periphery into a bright city.” This was the beginning of their collaboration, which Di Segni recounts in his book Dal tramonto europeo alle luci di Gerusalemme (From the European Dawn to the Lights of Jerusalem).

In this memoir, the author captures the evolution of the entire country from an original point of view: that of an electrical engineer who joined the public lighting system by chance, but ended up becoming its director. “We reached 45,000 points of light in the city of Jerusalem, compared to 7,000 in 1970,” recalls Di Segni in one of the last chapters of the book. A painstaking work that reached every corner of the city, gradually transforming it. Together with the author, we walk through the streets, monuments, houses and gardens of Jerusalem. Through personal reflections, memories, and technical insights, we get an architectural and historical map of the city and the events that shaped it.

Di Segni recalls, for example, the 1973 Yom Kippur War as one such moment. “One of our tasks was to turn off all the street lights every evening and create a total blackout. It was a time of great tension, but also of opportunity. “In those days, together with engineer Stroumsa, we decided to take advantage of the quieter routine maintenance work to improve the electricity grid!”

Work was also the place where the different souls of the city came together. “In terms of working relationships with colleagues of different ethnicities and religions, I always tried to be fair and, above all, to respect the Arab employees,” says Di Segni. “There was never a problem between us, neither between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, nor between Jewish and Arab workers.” The common effort was to bring light to Jerusalem, even in dark times.

Translated by Chiara Tona, student at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainee in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche.