BOOKS – Lidia Rolfi, partisan teacher

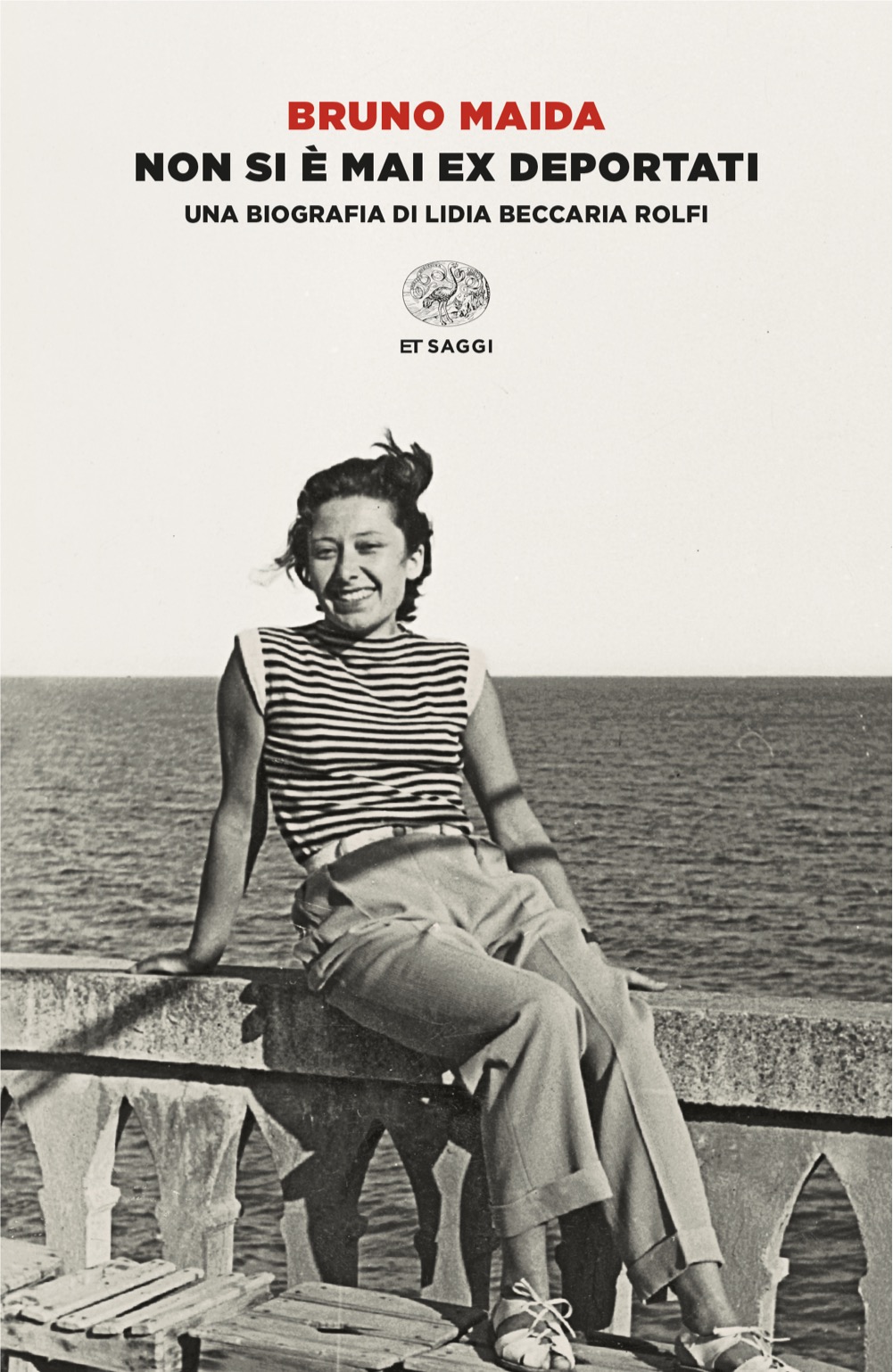

Lidia Beccaria Rolfi, an elementary school teacher and partisan relay, was arrested in 1944 at just 19 years old and deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp. She would have turned 100 on April 8 of this year. Onthat day, publisher Einaudi brought to bookstores Non si è mai ex deportati. Una biografia di Lidia Beccaria Rolfi (You Never Become An Ex-Deportee. A Biography of Lidia Beccaria Rolfi), a book in which the historian Bruno Maida expands upon the biography he had published with UTET many years ago. “I have always considered Lidia Beccaria Rolfi’s story to be exemplary story in many ways,” Maida explained to Pagine Ebraiche. Her trajectory “spanned 70 years of history, and I like to define her as ‘a twentieth century woman’, one of those women who started off as young fascists, and later gained new awareness and had a brief and irrelevant experience as a partisan in Val Varaita. This was as irrelevant as many others’, including Primo Levi’s. The two will become friends in the 1950s. Their stories were almost parallel. After the war, they both publicly shared their stories and developed a friendship made of messages that are published in this book for the first time.”

“I have always considered Lidia Beccaria Rolfi’s story to be exemplary story in many ways,” Maida explained to Pagine Ebraiche. Her trajectory “spanned 70 years of history, and I like to define her as ‘a twentieth century woman’, one of those women who started off as young fascists, and later gained new awareness and had a brief and irrelevant experience as a partisan in Val Varaita. This was as irrelevant as many others’, including Primo Levi’s. The two will become friends in the 1950s. Their stories were almost parallel. After the war, they both publicly shared their stories and developed a friendship made of messages that are published in this book for the first time.”

A professor of contemporary history at the University of Turin, Maida has already published several volumes with Einaudi about children in the Shoah and has long worked on the figure of Lidia Beccaria Rolfi. “The historian Anna Bravo, who mentioned Beccaria Rolfi in her book Donne del Novecento (Women of the Twentieth Century), supported by the Senate, used to call her “the great disrupter.” It is a description with which I strongly agree. While interned, Rolfi recorded her experiences in notebooks that are among the few direct testimonies we have. She later spoke about her experience in the lager as a sort of university, a way of saying that Levi made his, thanking her publicly.

“In the book Le donne di Ravensbrück. Testimonianze di deportate politiche Italiane (Women of Ravensbrück. Testimonies of Italian Political Deportees), published in 1978, Rolfi let other women speak: It is a milestone of storiography and of the memory of Ravensbrück; it was the first to be published in Italy. In L’esile filo della memoria. Ravensbrück, 1945: un drammatico ritorno alla libertà (The Slender Thread of Memory. Ravensbrück, 1945: A Dramatic Comeback to Freedom) published by Einaudi in 2021, Rolfi decided to publish her notebooks. It is an important work that sadly had limited circulation because of the pandemic.”

Maida describes Lidia Rolfi as an independent and autonomous woman who went against the grain. She reclaimed the centrality of women’s role, which is always denied. She reclaimed it and accepted the price, first as a partisan and then within partisan organizations, which have always been known for being sexist. “Many beautiful stories intertwine around this book,” added Maida.

“She was a strong woman who was curious about others and cared deeply for them. She showed this generosity even in the last part of her life, when she was very ill. She used to go to Cuneo, Piedmont, for chemotherapy, and there she started collecting the memories of other terminally ill women. She used to say that there was a parallel with her experience in the Lager and that it was the right thing to do to preserve their stories. We should find a way to honor her generosity towards life.”

Translated by Chiara Tona, student at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainee in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities– Pagine Ebraiche.