Emptied Jewish Homes, the History of Fascist Confiscations on display at the Shoah Memorial in Milan

A one-drawer walnut wardrobe, two twin beds with metal frames, a firwood table, five mismatched chairs, three frames with photographs. It is a dry, typewritten list. It ends with a total: 6,050 lire. An appraiser from the Monte di Credito su Pegno (Pawn Credit Bank) drew up this inventory on October 26, 1944. The location was an apartment in Via Casella 41 in Milan. These items belonged to Lea Behar. By the time officials entered the home, Lea and her daughter Sara had already been deported and murdered in Auschwitz.

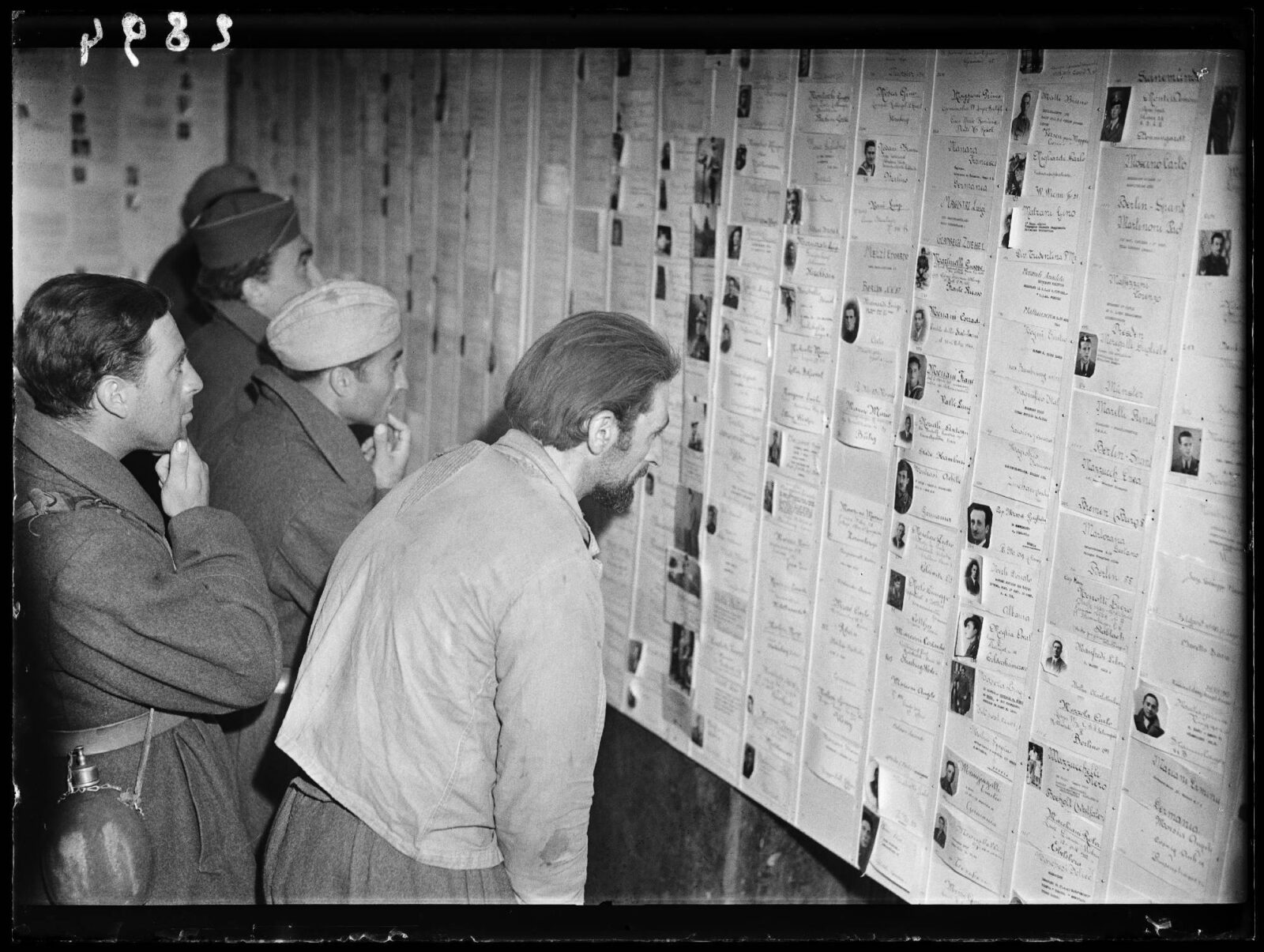

The document is part of the Egeli Collection, the archive of the Real Estate Management and Liquidation Authority created by the Fascist regime in 1939. Its purpose was to manage and liquidate property confiscated from Italian Jews. These papers reveal a silent and methodical violence, stripping away everyday life, room by room and piece of furniture by piece of furniture. They are now at the heart of the exhibition The Economic Persecution of the Jews. Life Stories from the Intesa Sanpaolo Historical Archive, which opened on January 20 at the Milan Shoah Memorial.

The story of Lea Behar and her daughters, Sara and Stella Dana, is one of three chosen to illustrate the economic persecution carried out by the Fascist regime. When the appraiser entered their apartment on Via Casella, Stella was the sole survivor, rescued by a Muslim family.

After the war, she attempted to recover those belongings by submitting a certificate from the Jewish Community of Milan to Egeli, attesting to the deportation and death of her mother and sister. However, it was not enough; the objects went up for auction, and the state absorbed the proceeds.

Alongside the Behar–Dana family, the exhibition follows the stories of the Colorni and the Levis families, three different trajectories united by their shared experience of being victims of the cold, persecutory bureaucracy set up by Fascism. “Thanks to the Egeli Collection inventory carried out by Intesa Sanpaolo in 2018, a new chapter has opened at the Memorial,” explained Barbara Costa, head of the Intesa Sanpaolo Historical Archive and curator of the exhibition. “It concerns a topic that, for many years, was considered secondary to the persecution of lives: economic persecution. It took concrete form in the confiscation of all Jewish property, from real estate to everyday objects.”

“The Historical Archive thus makes available documentation of great historical relevance. Not only for scholars, but above all for the new generations, for whom this exhibition is intended,” Costa added.

The documentation consists of over 300 folders and 1,400 individual files. They provide insight into the home and private lives of the persecuted families. These lists record not only the economic value of the goods. They also reveal the families’ habits, tastes, and relationships.

“These papers are almost always used in a negative way, to tell the story of dispossession,” economist Germano Maifreda told Pagine Ebraiche. Maifreda is the author of the book La memoria restituita: Storie di Imprenditori e Dirigenti Ebrei Nell’Italia delle Leggi Razziali (Memory Returned: Stories of Jewish Entrepreneurs and Executives in Fascist Italy under the Racial Laws) recently published by Il Sole 24 Ore. “I am also interested in using them positively, starting again from the objects and homes to understand how Italian Jewish families lived before the racial laws.”

The inventories include home libraries, bourgeois furnishings, work tools, and toys. However, the absences are striking as well. “We rarely find the most precious objects, which had economic, emotional, and symbolic value, because they were often moved or hidden. Sometimes they were entrusted to neighbors, who returned them after the war.” For Maifreda, “the list of objects has an almost pedagogical value because it immediately humanizes.” It is no coincidence, he added, that the Italian Social Republic went so far as to ban the publication of these lists because it understood their power.

The documents show that the postwar period does not always coincide with restitution. For many survivors, the procedures are lengthy. They are costly. They are often humiliating. In some cases, they are never initiated at all. “The absence of restitution is also a historical fact,” Maifreda emphasized. “Some people give up. Some do not want to reopen that wound. Some never return home at all. It is a second erasure.”

Translated by Matilde Bortolussi and revised by Alessia Tivan, students at the Advanced School for Interpreters and Translators of the University of Trieste, trainees in the newsroom of the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities – Pagine Ebraiche.

d.r.