When comics were home for the outcasts

Since the early days of comic book publishing, Jewish and Italian-Americans have been working side-by-side to create an alternate universe where differences are celebrated. Comics create a home for those who feel like outcasts. Children identify with their superhero counterparts as they face similar struggles, making them feel less alone in the world. Through the writing and illustration of these books, artists brought awareness to social issues in an entertaining way. Most notably, throughout the twentieth century, Italians and Jews worked together on comics that condemned communism and dictatorships.

From the 1880s to the 1920s the United States experienced concurrent influxes of Jewish and Italian immigrants. In their native countries, both groups faced poverty and political turmoil which made immigrating to America a promising alternative for millions. However, when they arrived they faced the same hardships that most immigrants do, including growing nationalist and anti-immigrant cultural currents and politics. Many immigrants felt isolated in a place that was supposed to be welcoming.

As a young generation of Jews and Italians was born in the US, and experienced much of the hostility their immigrant parents did, they began reading comic books, where they were able to identify with the characters whose differences made them into heroes. These comic books inspired many Jewish and Italian children to pursue art and try to create their own narratives.

In the early 20th century, there was a significant number of Jews and Italians working together in the comic book industry. This was in part a result of both groups feeling like outsiders. As Danny Fingeroth, former editorial director of “Spider-Man” put it, “You had a bunch of young men whose parents were immigrants, writing stories about a very idealized world, where force is wielded wisely and people are judged by their individual character, not by who they are or who their parents were”.

Notable Italians in the comic book industry were Carmine Infantino, Joe Orlando, Frank Frazetta, John Buscema and Frank Giacoia. They were active at the DC and Marvel publishers (both founded in the 1930s) and collaborated with Jewish artists, such as Jack Kirby and Jerry Siegel, on different comic books that entertained, but also informed youth about contemporary issues. The “Captain America” comics were created in part in order to aid America’s war effort. In fact, the first edition of “Captain America” shows the titular character punching Hitler in the face while German soldiers fired their guns.

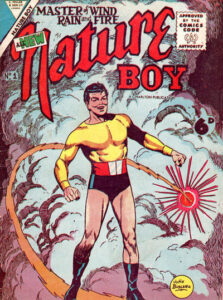

“Nature Boy”, written by Jerry Siegel and illustrated by John Buscema, is about a boy who calls on the forces of nature to help him fight crime. In “The Dictator of Utopia” Nature Boy is responsible for taking down a dictatorial town boss. Anti-communist and anti-dictatorial themes can be seen in many comic books, especially images of heroes challenging the Nazi regime.

The “X-men” comic book series, created in 1963, features the villain Magneto, as a Holocaust survivor. When he sees the way that normal humans react to mutants, he worries that a fate similar to that of the Jews in the Holocaust may await the mutants. This antagonist highlights the atrocities of the Nazi regime: Magneto is a character with a complex psychology, who develops a paranoia so great that it transforms the Holocaust survivor into the villain. By creating comics that explicitly condemned communism and totalitarianism, comic books influenced the way children thought about these political and social questions and provided them with an outlet for considering their own experiences.

As more kids read comic books parents began to worry that they might have a negative effect on their children. Dr. Lauretta Bender and Dr. Reginald Laurie published an influential early study on the effects of comics on children in 1941. The two authors interviewed children who were under some form of external stress, as a result of sexual assault, family disability, etc. The doctors found that through their reading of comic books, these children were able to identify with a hero in a world that would otherwise peg them as an outcast. Bender and Laurie write:

“This is not only in regard to the child’s attempt to understand his place in the world of modern science, warfare, and social organizations. It is also respecting his striving as an individual to solve his own everyday problems of right and wrong regarding aggression against him and his own impulses for aggression, counterbalanced against overwhelming feelings of inadequacies and inferiorities engendered by the lack of security in his own surrounding family relations and physical means”.

These findings bolstered the claim that comic books provide a creative outlet for children as well as a way for them to deal with their trauma or outcast status.

The strong presence of Jews and Italians in the early comic book industry shaped the development of the genre as well as the minds of their readers. The explicit condemnation of totalitarianism and intolerance in many of these publications informed the children that read them. Comics also helped by making children feel like they belonged in a world where they did not fit in. The common immigrant experiences of Jews and Italians in the US inspired them to create the comics that have shaped the minds of generations of American children.

(Above, Nature Boy, a superhero created by Jerry Siegel and drawn by John Buscema. He first appeared in March 1956. In the story “The dictator of Utopia”, he takes down a dictatorial town boss)

*This piece is part of a series of articles written by students of Muhlenberg College, Pennsylvania, USA, enrolled in a course on the history and culture of Jewish Italy, taught by Dr. Daniel Leisawitz, Assistant Professor of Italian and Director of the Muhlenberg College Italian Studies Program.