CULTURE – The Bemporad family and the cookbook that united Italy

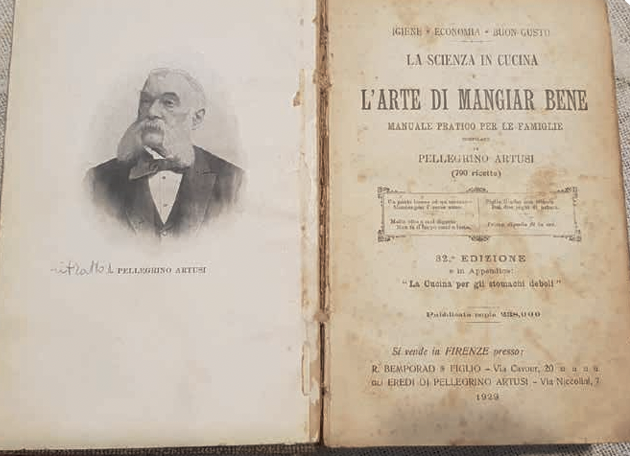

At the end of the 19th century, Italian gastronome Pellegrino Artusi knocked on the doors of various publishers to get his cookbook published. He tried, among others, to persuade Emilio Treves, the man who at that moment embodied Italian publishing. Yet Treves dismissed him: “We don’t deal with cooking.” Another prominent publisher, Ulrico Hoepli, was interested but imposed too onerous conditions. Artusi was consequently forced, at least initially, to publish his Science in the kitchen and the art of eating well at his own expenses. The recipe book was released in 1891 and the thousand copies printed went all sold. This was not a significant achievement, even for then-illiterate Italy, but still a sign of a potential market. Ten years on, a friendlier publishing house, Bemporad of Florence, would consecrate Artusi’s work.

Between the Jewish Italian publisher Roberto Bemporad, his wife Virginia Paggi, and the author of Science in the kitchen, there was a strong friendship. The Bemporad couple suggested to Artusi, as he wrote, “a dish of Arab origin that the descendants of Moses and Yakov” had “brought around the world,” and that in Italy was used “by the Israelites as soup.” Most likely, it was still the Bemporad family, as Tommaso Munari recounts in his book L’Italia dei libri. L’editoria in dieci storie (The books’ Italy. Publishing in ten stories), who introduced their friend to the versatility of eggplant, a vegetable “neither windy nor indigestible” that in mid-19th century Florence was regarded “as lowly, being food for Jews.”

In addition to making suggestions, the Bemporad family’s publishing house deserves credit for believing in the book rejected by Treves and Hoepli.

The Bemporad publishing house strongly believed in the book. So reads its advertising: “It often happens that two people joined by God and the mayor in matrimony are separated by a poorly prepared stew, a mutton leg not properly roasted, or a badly boiled piece of beef.” “How to avoid separation?” writes Munari. Rushing to buy “the book by Mr. Artusi, inspired by the triple concept of hygiene, economy, and good taste.”

The advertising gimmick worked, and by the early 20th century, La scienza in cucina became an increasingly popular book. In the following years, Munari explains, the cookbook became a symbol of Italian unity. So much so that the writer Giuseppe Prezzolini concluded his course at the Columbia University in New York titled Contributi dell’Italia alla cultura europea (1938-39) by citing Artusi. In the 1970s, an editor at Einaudi would say: “Artusi is as important to the culinary field as Manzoni is to the literary field.”