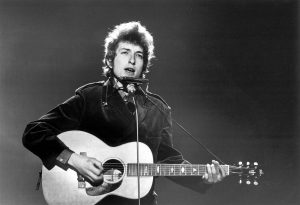

MUSICA E LINGUAGGI Bob Dylan, capire le parole

Più di mezzo secolo di storia della musica. E della poesia. È infatti dal 1962, anno di uscita del suo primo album, che Robert Allen Zimmerman, il Nobel per la Letteratura 2016, usa i testi delle sue canzoni per evidenziare il suo aderire all’una o all’altra delle tante identità che si è scelto nel corso della lunga carriera. È impossibile procedere a un’analisi sistematica dei suoi testi, che hanno attraversato contesti storici e culturali incredibilmente diversi, come diversi sono stati gli stili musicali a cui ha fatto riferimento, anche se cercare di capire quali siano state le sue fonti di ispirazione è sicuramente interessante.

Più di mezzo secolo di storia della musica. E della poesia. È infatti dal 1962, anno di uscita del suo primo album, che Robert Allen Zimmerman, il Nobel per la Letteratura 2016, usa i testi delle sue canzoni per evidenziare il suo aderire all’una o all’altra delle tante identità che si è scelto nel corso della lunga carriera. È impossibile procedere a un’analisi sistematica dei suoi testi, che hanno attraversato contesti storici e culturali incredibilmente diversi, come diversi sono stati gli stili musicali a cui ha fatto riferimento, anche se cercare di capire quali siano state le sue fonti di ispirazione è sicuramente interessante.

È probabile che uno degli autori che hanno più influenzato gli inizi sia stato Woodie Guthrie, il musicista, cantautore e scrittore statunitense considerato fra i più importanti della storia della musica del paese, autore di quei blues parlati che furono precursori delle canzoni di protesta più note. Bob Dylan, originario del Minnesota, iniziò a imitarne le strutture del discorso, tipiche dell’Oklahoma e raccontate nella biografia di Guthrie “Bound for glory”, al punto che nel 1961 a un concerto che tenne a New York, disse al pubblico di aver “viaggiato per il Paese, seguendo le orme di Woodie Guthrie”. Ma il Minnesota non ha la stessa tradizione di musica folk dell’Oklahoma e degli altri stati delle grandi pianure, né lo stesso accento vagamente metallico e una simile scelta può essere dovuta solo a una volontà di Dylan di integrarsi nella sena del folk. E Song to Woody è ancora, a più di cinquant’anni di distanza, una delle sue canzoni più note, e uno dei tributi più alti alla tradizione folk americana.

“I’m seein’ your world of people and things

Your paupers and peasants and princes and kings

Hey, Woody Guthrie, but I know that you know

All the things that I’m a-sayin’ an’ a-many times more

I’m a-singin’ you the song, but I can’t sing enough’

Cause there’s not many men that done the things that you’ve done”

E in particolare le parole:

“Here’s to the hearts and the hands of the men

That come with the dust and are gone with the wind”

parrebbero essere una risposta a un verso di Guthrie (in Pastures of Plenty):

“I worked in your orchards of peaches and prunes

I slept on the ground in the light of the moon

On the edge of the city you’ll see us and then

We come with the dust and we go with the wind”.

Dylan Thomas è stato un altro riferimento forte, anche se in maniera forse meno evidente, e nonostante fosse una voce in circolazione già da tempo solo nella sua recente autobiografia

Chronicles Bob Dylan ha riconosciuto nel poeta gallese il motivo del suo nome d’arte, adottato alla fine degli anni Cinquanta.

In un’intervista recente, poi, ha dichiarato: “You’re born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free”. per ribadire, nel documentario No Direction Home, girato nell’anno successivo (il 2005) che “I didn’t really have any ambition at all. I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be, and so, I’m on my way home, you know?”

Più difficile è ricostruire quali esattamente siano state le poesie di Dylan Thomas che hanno influenzato Bob Dylan, ma forse una risposta può essere trovata guardando agli argomenti, più che ai versi: nel poema And death shall have no dominion:

“And death shall have no dominion.

Dead man naked they shall be one”

L’argomento è affrontato in maniera potente, che forse si rispecchia nella canzone Let Me Die in My Footsteps, del 1962:

“I will not go down under the ground’

Cause somebody tells me that death’s comin’ ’round”

Mentre in The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll (registrata nel 1963) il riferimento al conflitto sulla morte è più ovvio, e lascia trasparire il tentativo di trovare un senso in un assassinio assurdo.

Forte, e simile a quello del poeta Gallese, anche il linguaggio che Dylan ha usato in un’altra delle sue prime canzoni: in Oxford Town (1963), che racconta del primo studente nero iscritto alla University of Mississippi, canta:

“He went down to Oxford Town

Guns and clubs followed him down”.

Mentre in Masters of Wars, una protesta contro la corsa agli armamenti dovuta alla Guerra fredda, scrive:

“Come you masters of war

You that build all the guns

You that build the death planes

You that build the big bombs

You that hide behind walls

You that hide behind desks”.

I primissimi album di Dylan comprendono soprattutto canzoni di protesta, presto adottate dal movimento americano per i diritti civili. Del suo secondo album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, è parte la famosissima Blowin’ in the Wind, con la nota serie di domande retoriche e universali su guerra, libertà, diritti e sulla pace cui l’unica risposta possibile è

“The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind”.

In Talkin’ World War III Blues torna il riferimento a Guthrie con il “talkin’ blues style” che era sua caratteristica più popolare, e nel 1965 realizza il suo quinto album, Bringing it all Back Home, in cui compaiono sia strumenti acustici che elettrici, in un allontanamento dalla tradizione folk che però non è così forte nei temi e nei testi delle canzoni. Di quell’album è parte It’s Alright, Ma (I’m only Bleeding), considerata uno dei suoi capolavori, e in cui Dylan scrive:

“Disillusioned words like bullets bark

As human gods aim for their mark

Make everything from toy guns that spark

To flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark

It’s easy to see without looking too far

That not much is really sacred”

Qui si scaglia contro consumismo e società dei consumi, contro cultura e valori americani. Non una vera e propria canzone di protesta, ma un atto personale di accusa contro l’establishment, perché, come ha poi detto in un’intervista del 2004: “morality has nothing in common with politics”.

Tornando a Guthrie, è a lui che è dedicato un testo registrato nel 1963:

“When yer head gets twisted and yer mind grows numb

When you think you’re too old, too young, too smart or too dumb

(…)

You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You’ll find God in the church of your choice

You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital

And though it’s only my opinion

I may be right or wrong

You’ll find them both

In the Grand Canyon

At sundown”

La prima e unica registrazione di questo testo è stata resa nota nel ’91: l’eredità del cantore di un’America che non esiste più era rimasta con Dylan, un’emozione troppo forte per essere condivisa. Un poema che non è mai più stato portato in scena.

Ada Treves